Though denialism remains in vogue (for now), there is overwhelming evidence for a true, devastating increase in autism, a surge that began with births in the late 1980s and has continued unabated.

From Figure 8, showing the exponential increase in the autism caseload in the California Developmental Services system, which is limited to cases of “developmental disability” type autism and omits most cases of high functioning autism.

By Jill Escher

When it comes to the question of autism trends over the past several decades, it is undisputed that the prevalence of diagnosed cases has grown dramatically, in the range of .01-.05% for children born in the 1950s to about 3% for children born more recently, at least in industrialized countries like the U.S., the U.K., Australia, South Korea and Japan [Figure 1].

While no one in the field seriously disputes these numbers, a debate continues to rage over whether this 60-fold increase is owing to an actual epidemic of abnormal brain development in our children, or a mere conceptual evolution resulting in re-labeling of mental conditions that have always been around, or a combination of these two factors.

Based on a reading of studies spanning seven decades and more than a dozen countries, reams of administrative data, as well as expert interviews, I can see only one resounding conclusion: the evidence is overwhelming for a true, torrential increase in autism, beginning with children born from the late 1980s and accelerating in an exponential manner through today. Even comparing apples to apples without incorporating a broader definition of autism into the scope of comparison, the data reflecting autism’s ascendance are Mt. Everest in scale compared to the molehills of the contrary arguments. Might some broader inclusion influence rates somewhat in some systems? Sure, but this cannot possibly explain the seismic shifts over the past three decades.

To explain, I’ll go over both the evidence for a true increase and the arguments against it. While it’s impossible to address all the many evidentiary threads I’ll try to hit on some highlights.

Evidence for a true increase

Let’s examine evidence for autism’s increasing rates through three basic modes of exploration, from the most casual to the most scrupulous: common-sense observation, administrative data, and epidemiological studies.

1. Common-sense observation

Observations may not amount to objective science but they are relevant to the overall picture and a worthy component of critical thinking that should considered in any discussion of public health trends. For example, it’s hard to miss that relative to today, few Americans were obese in the 1970s, based on collective memory and photographic/video evidence. While observations like these are hardly gold-standard evidence, reasonable people can observe such a trend and allow it feed into their truth algorithm, while at the same time being open to contrary evidence that may flow from careful research. If 3% of babies are born with blue hair, and we’re pretty sure we hadn’t seen that in generations past, we’re allowed to employ basic logic to conclude it’s highly likely a new phenomenon, but again subject to contrary evidence from carefully conducted studies.

With that in mind, let’s run an observational logic experiment based on the overview of the explosion in childhood autism prevalence seen in Figure 1. According to the latest U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) network data, among U.S. children with autism an estimated 35.2% also have intellectual disability (ID) (IQ≤70), 23.1% have borderline ID (IQ 71-85), and 41.7% have average or higher IQ (IQ>85). For the sake of argument, let’s put aside the 41.7% with average or higher IQ as possibly going without any label in the past (which is unlikely, but again, for the sake of the thought experiment). That leaves 58.3% of cases that would likely not have been overlooked in the past. Now look at Figure 2. If there has been no true increase in autism, we would have to believe practitioners and researchers missed all the green cases of autism in the 1950s. That amounts to about 1.75% of all children, less 0.05% who were identified, for a total of 1.7% of all children that no one noticed were substantially disabled by autism (or any related label). Is this remotely possible? We are allowed to be highly skeptical that throughout the modern era that skilled practitioners missed such a massive number of affected children.

In the same vein, if today’s autism rates existed in the 1940s, we should be questioning whether it’s possible that in his landmark 1943 paper first describing autism, renowned child psychiatrist Leo Kanner could have characterized his 11 novel cases as something “markedly and uniquely different from anything reported so far” — and also see none of his peers laughing at his assertion. Again, even if we are to limit autism just to cases with ID or borderline ID, that would be 1.75% of all children. Did the entire field of psychiatry miss seeing observably disabling autism in 1.75% of all children? This is a preposterous notion. The most rational take on the situation is that Kanner and the psychiatric profession considered autism to be extremely rare because back then, it was. Even in the 1970s, when researcher Lorna Wing insisted on an expanded view of autism, she contended autism was not about 0.04% as thought in the U.K. as found by careful field studies, but maybe four times higher, at least in the London area. However, Dr. Wing’s maximum of .16% still falls extremely short of today’s 3%, or even the stricter-definition 1.75%.

We are often told that children with autism existed in these numbers but were hiding under other labels, such as “feeble-minded,” or later, “childhood schizophrenia” or “mental retardation,” or that they were hidden away in institutions and left uncounted. But there is no evidence for these contentions.

The U.S. Census of 1890 found 95,609 “feeble-minded” persons of a population of 62,979,766, for a total of 0.15% of the population. It was later estimated that about 55,000 individuals had not been counted, but that would barely move the prevalence rate. It is interesting to note that the Scotland census of 1891 found a similar rate; just 0.125% of the population were “imbeciles.”

As for old diagnostic labels, the historic rate of childhood schizophrenia was vanishingly low and could not come close to accounting for the high rate of autism today. For example, a landmark study of U.S. children born in the early 1960s, the multi-site Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP) study found only 6 out of 30,000, or 0.02% of children evaluated for mental health outcomes had childhood schizophrenia or related mental disorders. A 1970 study by Donald Treffert found even lower rates of childhood schizophrenia among children in Wisconsin. As for the argument that a diagnostic shift from Mental Retardation/Intellectual Disability explains escalating rates of autism, that will be addressed later in this essay.

Regarding institutions, we often hear that rates of autism were low in the past because such people were hidden away in institutions. In fact, in 2014 I met with an autism clinician named Bennett Leventhal at his office at UCSF. He crossed his arms and said, “I assure you, Jill, there has been no true increase in autism,” and then proceeded to sketch on his whiteboard a house with stick figures both on the bottom floor and in the attic. The kids in the metaphorical attic just weren’t counted, he argues. But Dr. Leventhal’s view does not comport with reality. The percentage of people with autism sent to institutions was extremely small compared to the 3% prevalence we see today. California’s Department of Developmental Services (CalDDS) counts about 190,000 cases of developmental-disability level autism today, but in 1964, at the height of the period of institutionalization in the state, there were about 13,000 people with developmental disabilities residing in the developmental centers, and another 3,000 on waiting lists. Keep in mind the 13,000 was composed of a diverse population with Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, brain injury, ID, and genetic disorders, in addition to autism. Autism would have been at the absolute highest possible estimate a few thousand cases. Today’s CalDDS autism population dwarfs any possible earlier institutionalized population, even accounting for the doubling of the state population over that time. The CPP data are also illuminating. Of the CPP’s 40,000 children born in the early 1960s, only about 125 children were institutionalized, for total of 0.31% of children. As with the California institutions, those would have comprised a wide variety of mental disorders, not just autism. And going back in time to the U.S. 1890 Census, only 5,254 of the enumerated 95,609 feeble-minded individuals were in institutions for the feeble-minded and 2,469 were in insane asylums.

The most obvious observational logic question, though, is this: if autism has always been around, and at these rates, we would see a commensurately high rate of senior citizens with autism in group homes, day programs, hospitals or other services or accommodations. But we don’t. There is not a single eyewitness account or data source, anywhere, showing anything remotely like a 3% autism rate among seniors. Community observations on this point are worthy of consideration, and here’s one. Sue Swezey, a mother of a son with autism and a co-founder of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area, shared in a blogpost that her son John, now 61 years old, was born in 1963 (back when studies found autism rates to be about 0.01-0.05%). She says in the 1960s and 70s that John “was a little boy very much alone with his diagnosis,” that people “had never seen anyone like him before,” and that nobody doubted the research-established prevalence rate. John’s first and second school districts both counted only one other child with autism (these districts now have hundreds of students with autism sufficiently severe to qualify for special education). There were so few autism families that when advocating at the state capitol the handful of autism parents resorted to wigs and wardrobe changes to appear more numerous. I should also add that I’ve known John for years and he is considerably higher functioning that my own two children with autism and hundreds others I know just here in our region, so I find it ridiculous to think that innumerable cases even more severe than John were overlooked.

John is now a senior citizen with few autistic peers his age. Based on data from the CalDDS, as of 2016 the entire statewide system counted just 146 clients with autism born in his birth year of 1963. Please compare that to the 5,163 CalDDS autism cases born in 2010. Where are the thousands of missing autistic 61 year-olds like John? There is no evidence they exist; the CalDDS data doesn’t even have them showing up as “ever” in the system, not just active cases. If one is going to argue an “always been here” position, one should at least offer some data demonstrating this torrent of allegedly overlooked cases, whether from psychiatric, school, military, hospital, welfare or other systems. But no one has ever been able to produce such data.

Community service providers are also a trove of historical wisdom. Having spoken with more than a dozen developmental disability providers in the San Francisco Bay Area over the years, their chorus is also uniform: for decades they had a steady caseload of Down syndrome, other genetic disorders, cerebral palsy, brain injury, and intellectual disability, and occasionally, autism. Then in the 1990s they saw a rapid upswing in the numbers of children with autism, and in the 2000s they began noticing a strong surge of young adults aging out of the school system, not just with the label of autism but also with qualitatively different characteristics of autism, such as limited language, weak social skills, cognitive inflexibility, and disruptive and dangerous behaviors. The new crop of young adults with autism were more challenging and costly to serve, an observation backed up by CalDDS expenditure data. The service providers struggled. The budgets and staff could not keep up, a trend seen across the nation, as the providers helplessly witness an unprecedented annual “firehose of autistic 21 year-olds” (as one New Jersey housing provider recently put it) desperately needing adult programs. Alex Krem, whose family has run camps and recreational programs for children and adults with developmental disabilities in Northern California since 1961, hardly saw any autism cases until the 1990s, and now the program’s entrants are mostly child and young adult autism cases.

Autism is now constantly in the news, something we take for granted. But autism hardly made any headlines before the 1990s. Now we hear almost weekly about a child with autism who has wandered and drowned, a now-common tragedy somehow not noticed in news reporting before this century. We hear about new autism schools continually opening, when no one saw much need for these schools before the 1990s. We see story after story of families crying out for help, while officials say they are overwhelmed and can’t keep up with crushing waitlists. We see sensory hours at stores, sensory-friendly shows, autism parking spots, the need for enhanced police training, specially designed parks. Is this due to mere awareness, or a punishing burden of need? It seems impossible to me that the entire news industry missed reporting on this population for the entire history of our nation until the 1990s.

(As someone who has battled against the debunked vaccine hypothesis of autism, I am loath to refer to a website authored by one of its proponents, but we should give credit where credit it due. A website by Anne Dachel catalogues over 9,000 news stories relating to the growing rates of autism, especially in the schools. Though her suggested reason for autism’s ascendance is clearly erroneous, she is a helpful shepherd of an avalanche of stories reflecting the dire impact of the torrential and unrelenting increase of autism.)

Personally, I never saw or heard of a single person with autism, except the fictitious Rain Main, throughout my youth and young adulthood, until the diagnosis of my son Jonathan, born in 1999. When we sought a class for Jonny through our school district, the staff commented on the convulsive growth in autism they noticed in the recent years, an onslaught that seemed to come from nowhere. Jonny’s pediatrician, who had seen thousands of children over a long career, had not seen much autism either, under any label. I hear the same refrain from countless other old-timers in education and clinical services. A speech therapist friend explained how autism was barely part of her training curriculum in the 1980s because so few patients with that profile were ever seen. Even the former director of the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH), Dr. Thomas Insel, remarked: “When my brother trained at Children’s Hospital at Harvard in the 1970s, they admitted a child with autism, and the head of the hospital brought all of the residents through to see. He said, ‘You’ve got to see this case; you’ll never see it again.'”

The no-true-increase adherents are asking us to engage in collective amnesia. Not only are we allowed to invoke common sense observations about today’s autism population eclipsing that of previous generations by orders of magnitude, we absolutely must if we are to seek the truth. But now we are now barely off the starting blocks. Let’s move on to administrative data.

(2) Administrative data

Administrative data is a big step above casual observation. It generally refers to data kept by organizations and agencies that are tasked with providing some sort of service or keeping track of cases in a registry. Such data can come from many sources, including hospital and insurance systems, school districts, and safety net systems such as social security disability programs and state Medicaid programs. This data is usually limited to raw overall caseload or caseload by birth cohort, but sometimes is subjected to further analysis to derive birth year, or birth cohort, case count or prevalence.

Hospital systems. Let’s start with hospitals. The largest U.S. study of autism prevalence seen in hospital systems is via the nation-wide Mental Health Research Network (MHRN). Figure 3 shows the MHRN autism diagnosis rate grows higher with each birth cohort, with the exception of ages 0-4, which is likely explained by a usual lag in diagnosis. Autism in adults over age of 35 is shown to be extremely rare. Autism rates are about 2.8-3.1% for children aged 5-8 in 2022, consistent with the rate seen in the CDC ADDM network and other federal studies. Did these 12 large hospital systems all miss massive numbers of adults with autism? It seems unlikely to the point of impossible.

Schools. Schools in the U.S. keep robust autism data due to the 1975 federal special education law (now called the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act, or IDEA) mandating a free and appropriate public education for pupils with disabilities, including autism. The mandate only applies if the autism negatively affects the child’s educational performance and therefore typically does not cover the very mild cases; an autism case is included in special education data if the child requires extra supports or services beyond those in the general curriculum. Even given this limitation, autism cases in special ed have skyrocketed.

In California, the number of students with autism exploded, from 14,038 in the 2000-01 school year to an astounding 167,341 in 2023-24. That’s a 12-fold increase over 23 years, at a time of generally declining school enrollment in the state. Though it is often speculated that this surge can be explained by a diagnostic shift out of the ID category, the data show this to be untrue. The ID numbers remained flat over that time, around 40,000 for both of the those school years [Figure 4]. From a prevalence, as opposed to raw case count, perspective over a shorter period of time, just ten years between 2011 and 2020, we again see an autism surge while ID and other related categories held steady [Figure 5].

This same trend is seen in other states. For example, an older study was conducted in Minnesota on children aged 6 to 11 years by James Gurney et al. using a special education definition of autism. ASD cases had surged exponentially in the state beginning in the 1991 school year [Figure 6]. The researchers found ASD prevalence in this age bracket increased from 0.03% in 1991-1992 to 0.52% in 2001-2002, a 17-fold increase, while the other special educational disability categories also increased during this period, except for mild mental handicap, which decreased only slightly. With respect to the huge surge of ASD, the authors remarked that “diagnostic substitution does not largely explain the increasing trends.”

In 2019, Massachusetts reported that its schools were serving four times as many students with autism as it did 15 years prior. Just recently Wyoming reported a 60% increase in autistic children in early childhood education and a 19% increase in autistic children in K-12 schools, just since 2018. We can see reports like this from every state.

Nationwide data show that whereas less than 5% of disabled students in the U.S. had autism in 2008-2009, just 14 years later, by 2022-23, that number had jumped to nearly 13%. Based on somewhat earlier numbers from 49 states, the number of 6- to 21-year-old students classified as having autism rose 165% between the 2005-06 and 2014-15 school years.

Like the U.S., the U.K. schools have also experienced an enormous growth in autism cases. A 2020 report by Roy McConkey found massive increases in autism over nine years from 2010-11 to 2018-19 in schools in all four U.K. countries, noting that “the rate of increase shows little sign of abating and may indeed be accelerating.” Northern Ireland had the highest prevalence, reaching 3.2%. Just recently the Telegraph reported that the cost of supporting schoolchildren with special needs has jumped again by more than two-thirds since just 2018-19, from £6.9bn to £12bn, paralleling the increase in the number of students with autism.

In Australia, about 4% of seven- to 14-year-old students now have a primary diagnosis of autism, while between 6% and 10% of children have ADHD. As a consequence of the unprecedented numbers of students needing specialized supports, “Parents, teachers and advocates say education is at crisis point.”

Medicaid and SSI. In the U.S., the Medicaid system is the largest provider of adult supports such as personal assistance, habilitative day programs, and disability services in residential facilities such as group homes. Entry into this system varies somewhat by state but overall one can only obtain Medicaid developmental disability services where the state finds you suffer such a substantial functional disability that you are incapable of achieving many basics of daily living. Disability-based Medicaid is not available those who are merely quirky or who think differently. Even in this restricted system, comparing apples to apples, we see a dramatic surge in autism rates in younger birth cohorts, with prevalence of Medicaid autism cases more than doubling over 8 years for the 18-24 age group [Figure 7].

Similarly, the federal Supplemental Security Income system, which provides monthly welfare payments to income-qualifying children and adults with autism and other disabilities experienced a similar growth in autism cases. Adults with ASD represented a growing share of the total first-time SSI awards given to adults with mental disorders, with percentages increasing from 1.3% in 2005 to 5.0% in 2015. In 2015, 158,105 adults with ASD received SSI benefits, a 326.8% increase over 2005. Federal SSI payments to adults with ASD increased by 383.2% during the same period (totaling roughly $1.0 billion in 2015).

State Medicaid programs: California Department of Developmental Services. Finally, let’s look at the data from CalDDS, which is well known to be among the nation’s most comprehensive, both in terms of time horizon and case capture. This is due both to the state’s unique statute, the Lanterman Act, which has long mandated case-finding of and services for residents with developmental disabilities, as well as the state’s expansive population, now at 39 million, about the same as the entire country of Canada, and representing nearly 12% of the entire U.S. population.

Through the 1980s, the autism caseload was modest, edging up from about 3,000 cases. But in the 1990s the system saw a tremendous unexpected influx of cases, and the legislature grew alarmed. After commissioning a 1999 study that confirmed the reality of the increase, which could not be explained as a diagnostic artifact, by 2003 the state legislature enacted a rule tightening CalDDS eligibility requirements. This attempt to stop the tsunami of cases proved futile however, as ever-more autism cases with seriously disabling symptoms grew year over year [Figure 8]. Between 1989 and April 2024, the autism caseload grew nearly 60-fold, or 6,000%, while the state population grew only about 33% larger. When the U.C. Davis MIND Institute determined the CalDDS autism prevalence rate by birth year, it saw a dramatic increase from birth year 1980 to 2014 [Figure 9]. And raw birth year data from CalDDS, as of 2016, show a dramatic increase between birth years 1945 and 2010, from 10 to 5,163 [Figure 9a]. A more recent (July 2023) Public Records Act data request indicated 6,299 autism cases for birth year 2010 (reflecting the influx of additional cases between 2016 and 2023), rising to 10,095 cases for birth year 2017 [Figure 9b].

Figure 9a: CalDDS active autism cases by birth year for birth years 1945-2010, as of 2016. Source: California DDS pursuant to a California Public Records Act request from Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area.

Figure 9b: CalDDS active autism cases by birth year for birth years 1931-2017, as of end of 2022. Source: California DDS pursuant to a California Public Records Act request from Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area.

While some contend that this tremendous growth in autism cases is due to a parallel decline in ID cases in CalDDS, the numbers do not bear this out [Figure 10]. ID cases grew while autism cases also climbed. Finally, the enormous transformation in the composition of the CalDDS caseload cannot be missed, either in the trenches or in the data, with autism growing from a tiny slice of the developmental disability population in 1993 to about half in 2023 [Figure 11].

Overall, the data from our nation’s most populous state paints a dire picture. Autism cases have been rising dramatically since births in the 1980s, despite the enactment of stricter entry requirements in 2003. Because of the requirement that each autism case involve substantial functional limitations across three major life activities, CalDDS autism represents only the more severely affected of all the state’s autism cases. There is not a shred of over-diagnosis here, or in Medicaid or SSI. Yet even these subsets have exploded in numbers, a phenomenon that has not and cannot be explained by diagnostic shifts, awareness or broadening of any slight shifts in psychiatric criteria.

(3) Epidemiological data

While the observational and administrative evidence may be strong and consistent, these data are not considered as bullet-proof and reliable as numbers from epidemiological studies conducted by experts and which involve active case review, fieldwork and/or case-finding. So let’s comb through what the gold-standard studies have shown. Do they deviate from what we have already seen? No, they only strengthen the case. We’ll start with studies in the U.S. and then turn to international numbers.

U.S. Epidemiology. The first large-scale epidemiological study on autism in the U.S. took place across the state of Wisconsin in the mid-1960s, ascertaining autism in children aged 12. In a 1970 paper Donald Treffert and his colleagues found a prevalence rate of 0.01% (1 in 10,000). Critics contend that this low prevalence only reflected what we would today call profound autism, but let us note the obvious. The CDC ADDM data on the 2012 birth cohort pinned Wisconsin’s autism prevalence at 2.8%. Even if, for the sake of argument, we limit that 2.8% to the estimated 26.7% of overall autism cases that rise to the level of profound autism (the 26.7% of autism as profound autism proportion comes from a CDC study to be discussed below), that’s a prevalence of profound autism of 0.74% in Wisconsin’s 8 year-olds, which is 74-fold higher than the autism rate of the 1960s. Did Treffert and colleagues miss about 74 cases for each 1 they found? It’s simply not possible.

Around the same time as the Wisconsin study, the aforementioned Collaborative Perinatal Project, or CPP, found an autism rate of about 0.046% in the 30,000 seven year-old children who underwent mental health evaluations. The CPP was particularly thorough in finding even subtle cases that the educational and medical systems would not have captured. In a paper by Torrey et al. the 14 children with autism, three had IQ scores above 70 (71, 72, 73), four had scores below 70 (37, 45, 50 and 50), and seven were considered untestable. The paper also identified six additional CPP children who were labeled as severely disturbed, apparently psychotic, childhood schizophrenic or possibly autistic. Four had abnormal language development and abnormal affective human contact when younger, but at age 7 had normal neurological development. The other two children were said to be obviously abnormal. The IQs in this group were 54, 67, 78, 82, and two were not testable. So, for the sake of constructing an even more conservative comparison to autism today, let’s add all those into the CPP autism pile, for a total of 20 children out of 30,000, or a rate of 0.066% cases. If we label those as classic autism (again, they clearly were not in some cases), this puny rate is just a speck compared to today’s rate of profound autism, which is at least 0.5% of all children. The CPP data also do not suggest that autism cases were hidden in the MR category, as about 1% of the children were found to have MR, which is even lower than ID rates seen today.

In 1984-88, Edward Ritvo and colleagues undertook an epidemiological study of childhood autism in Utah. The group found 241 of 483 potential cases had autism, for a prevalence of 0.04%, and this included not just the most severe cases, as one-third had IQs greater than 70. To see if changing diagnostic schemes might increase these low rates, a 2013 study by Miller et al. re-ascertained the potential cases under DSM-IV, finding 64 additional children originally “Diagnosed Not Autistic” met the new ASD case definition, with the average IQ estimate in the newly identified group significantly lower than in the original group. The inclusion of new cases would not have significantly altered the .04% prevalence, however.

Incidentally, the CDC ADDM data on the 2012 birth cohort estimated Utah’s autism prevalence at 2.2%. Even if we limit for the sake of argument the 2.2% to the estimated 26.7% of cases with profound autism, that’s a prevalence of profound autism of 0.59% in Utah’s 8 year-olds, which is 15-fold higher than the fuller-spectrum autism rate detected in the 1980s.

Around the same time, a 1987 paper by Larry Burd and colleagues ascertained an autism rate of 0.033% in children in North Dakota (59 of 180,000 children). Of those, 21 met DSM-III criteria for infantile autism (0.012%) and the remainder had more broadly defined pervasive developmental disorders (PDD). I need not explain the difference between 0.033% in the 1980s compared to the 3.0% today.

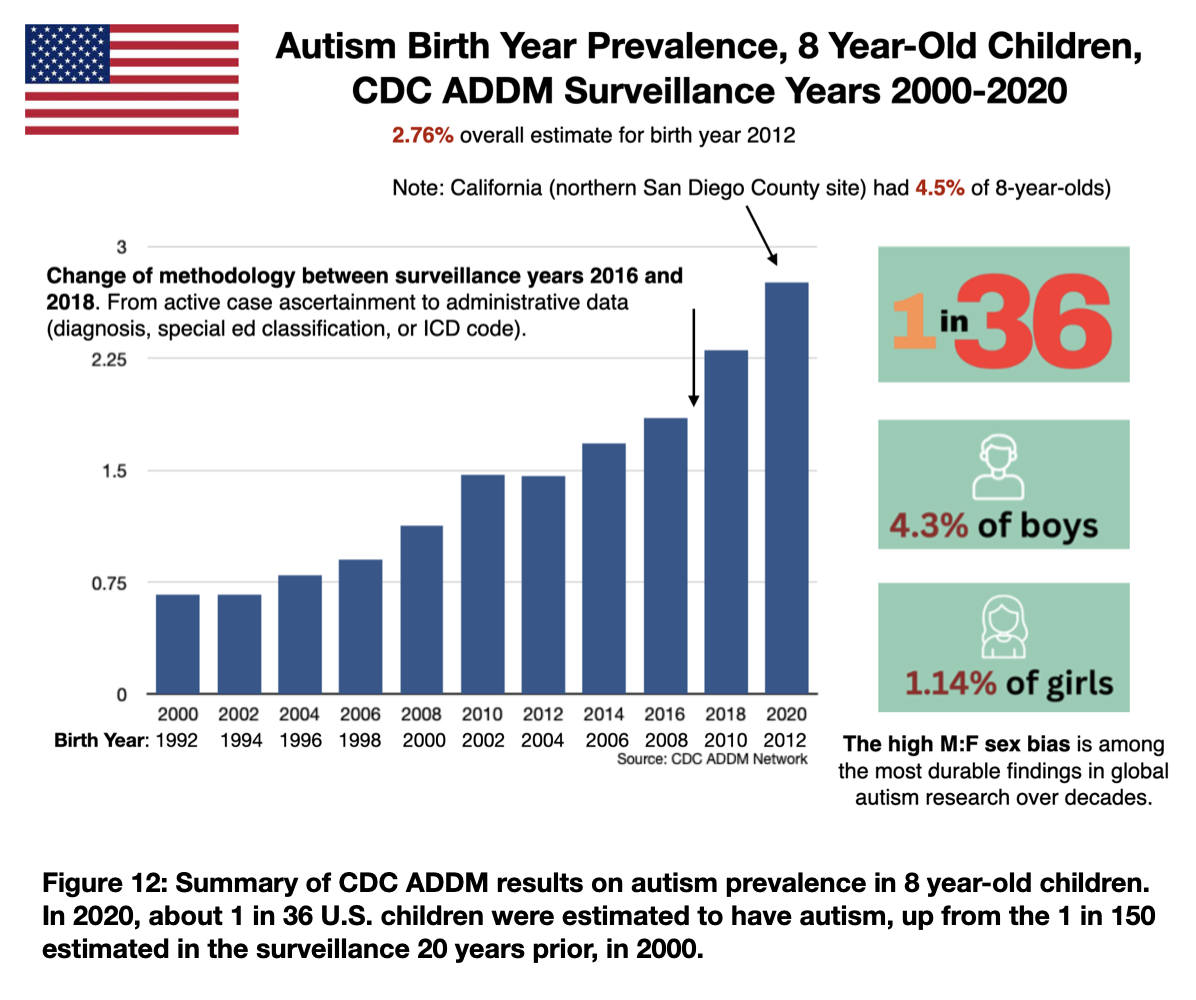

CDC Prevalence Studies. After years of the unexpected and dramatic increases in autism seen in clinics across the country, the CDC launched its first systematic childhood autism prevalence studies as part of the ADDM network, with 2000 as its first surveillance year examining children born in 1992 and who were then 8 years old. Ten additional ADDM cycles have been published, all employing fairly exacting methodologies in multiple different sites across the United States. The longitudinal prevalence results are summarized in Figure 12, with the most recent rate being 2.67% in 8 year-old children born in the year 2012 and ascertained in 2020 (another report from the ADDM will be released in March 2025).

As discussed above, an estimated 35.2% also have intellectual disability (IQ≤70), 23.1% have borderline intellectual disability (IQ 71-85), and 41.7% have average or higher IQ (IQ≥ 85). While it is true that rates of autism with Q≥ 85 have increased faster than the other two categories, one can easily see the sharp increases in autism in the other two, lower IQ, groups over time, a 2.4-fold growth in both analyses [Figure 13].

Nonetheless, all autism cases in the ADDM must meet clinical standards for autism, and case definition has been held constant over time. In the words of epidemiologist Walter Zahorodny, PhD, who has studied autism rates for a quarter century and serves a lead investigator for the ADDM site in New Jersey, autism under the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and often used in epidemiology “means an individual’s overall life functioning in practical circumstances is impaired or disabled, they have some significant deficit in being able to do expected things of their age.” He continues, “We never participated in the program as looking for autistic features or signs or personality characteristics—there are other disorders in the DSM which have elements of similarity to autism but not autism. Autism is not atypical social preference, but children who are easily recognized by experts as having a disorder.”

It’s important to note that at the end of 2016 the CDC shifted its approach to examine only already-diagnosed autism cases, rather than active case-finding which includes unidentified cases. The CDC moved to this less comprehensive system to improve speed and efficiency, and to respond to decreased funding allocated to autism surveillance and research. The 2016 cycle might be the last one to find as many cases as possible, not just those already diagnosed in the community. Nevertheless, despite the more lax methods, the ADDM autism numbers continued to climb in both the 2018 and 2020 surveillance years. In the 2020 surveillance the startling increase may partly be due to the inclusion of a California site in northern San Diego County finding an unusually high autism prevalence of 4.5% 8 year-olds. But on the other hand, the overall ADDM prevalence estimate was 2.76%, which is less than the prevalence reported in other federal studies. The CDC’s National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a comprehensive health survey of U.S. families, found that for children in 2022, 3.79% had been identified with autism. The 2019-2021 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) indicated higher a rate as well, finding about 3.1% had been diagnosed as having autism.

It is often repeated that over the course of its existence the CDC ADDM found an increase in autism prevalence growing from 0.67% in surveillance year 2000 (birth year 1992), to 2.76% for year 2020 (birth year 2012). But it’s worth noting that the CDC conducted a study on a 1988 birth cohort as well, as part of its Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program (MADDSP) (Van Naarden Braun et al 2015), using similar methods. The researchers found prevalence for birth year 1988 to be 0.42%. When the MADDSP prevalence grew to 1.5% in the 2002 birth cohort (which was comparable to the rate found in the larger ADDM study), the authors only found plausible ID-to-ASD diagnostic substitution for non-hispanic black females, a small subset of the autism population. Figure 14 shows the tremendous growth in autism while other disabilities remained flat or, in the case of ID, grew a moderate amount.

Finally, one must also consider that the CDC conducted a study to ascertain the prevalence of profound autism, which restricts the case definition to the most stringent criteria: typically involving an IQ under 50 and the need for round-the-clock care or supervision. Even with this intense restriction, we still see very substantial prevalence growth. Over just 16 years, 2000-2016, the prevalence of profound autism nearly doubled, from 0.27% of 8 year-old children to 0.46% [Figure 15]. And as mentioned before, 26.7% of all the 8 year-olds with autism were estimated to suffer from profound autism.

New Jersey epidemiology. Perhaps more than children in any other state, New Jersey children have been the subject of rigorous autism epidemiology over the past two decades, both as part of the ADDM and other efforts. The 2020 ADDM surveillance of 8 year-olds found an overall prevalence of 2.9%, up from 0.9% two decades prior, a surge seen across all forms of autism and all demographic groups. Additional studies have added troubling nuance to these findings. In some counties, autism affected 5% to 7% of the pediatric population, including 5% in Ocean County and 7% in Toms River, based on 2022 reports. Dr. Zahorodny stresses that the same ascertainment strategies have been used to validate true autism cases across all studies. Despite the staggering growth in autism, about a quarter of cases in children and adolescents are un- or mis-diagnosed in the community. Even as late as 2016, one of five 8 year-olds who met criteria for autism did not have a community diagnosis. Among 16 year-olds as many as a quarter did not have a diagnosis. Minority or low SES cases are more likely to be undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, and they receive their first professional evaluation later than white children.

““It feels like some kind of science fiction,” Zahorodny told the Asbury Park Press. “To say that 7% of 8-year-olds in one school district — and 5% of 8-year-old boys statewide — have autism is shocking, but in reality, this is true. And it can’t be explained.”

From 2000-2010, across many studies in New Jersey, Zahorodny and colleagues found a strong positive association between wealth and autism prevalence. However, since 2010 they have found that this wealth gradient is reversed, finding greater rates in low- and middle-income communities. In the study of adolescents, 16 years old, 59% had other co-occurring neuropsychiatric disorders, 35% had ID, and one in four cases had been undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. ASD among adolescents was two times as common in high-income compared to low-income communities. Black and Hispanic more likely to have ID. In a sign of the stability of their methodology over time, autism prevalence estimates found at 8 years old were the same for the cohort at 16 years old.

International epidemiology. To explore data from outside the U.S., let’s start with studies from across the pond. The earliest studies of autism from the U.K. showed a prevalence of about 0.01-0.05% among children. Victor Lotter’s 1966 study of children aged 8-10 years attending schools in England’s Middlesex county in the mid- 1960s found that 0.045% percent had autism, with only half of that group showing “nuclear autism,” meeting the criteria for Kanner autism, which perhaps is comparable to profound autism today. One-third had had IQ above 55. Wing and Gould's 1979 study looked for children with social impairment in Camberwell, London in the 1970s. Among this broader group, using the same criteria as Lotter’s study, the authors found 0.049% had autism, with slightly less than half of these showing “nuclear autism.”

Studies in the 1980s found a slightly higher prevalence of about 0.077%, using a broader definition of autism based on DSM-III, then the DSM-III-R criteria. But in the 1990s, things started going haywire, with a likely 0.1 to 0.12% rate, as reported by Gillberg and Wing in 1999. Using the most expansive criteria, the authors suggested a potential prevalence of 0.4% to 0.5% might even be possible. Successive studies have found steadily increasing prevalence since that time, up to 2023 when a study of children in England born 2004-2008 yielded a prevalence of 2.94%.

Stunningly, a group led by Ginny Russell of the University of Exeter found a dramatic increase in autism, 3.07% in 2018, but decided to self-censor the findings (see Ginny Russell, The Rise of Autism, 2021, pp. 20-21). An adherent to neurodiversity ideology, she writes: “In 2018, we re- estimated the percentage of children in the UK with autism using MCS [Millenium Cohort Study] data from when they were 14, an update from eight years old. The new number gave us pause for thought. We found a prevalence of 3.07% (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.64– 3.57) – higher than we had ever seen reported. If we simply reported what the data told us, we were concerned our estimate might be misinterpreted, as it seemed exceptionally high – too large an increase from eight years old. By misinterpreted I mean that people might read that autism rates had jumped, rather than that recognition (and possibly parental reporting) of autism had jumped. Although the increase might partly be due to more children being diagnosed after eight and before 14 years old, the increase was too marked to explain away completely and we decided not to publish our report. In a sense, we self-censored our findings.” [Emphasis mine.]

Moving beyond the northern border, Canada has not conducted longitudinal epidemiological investigations like the ADDM, but various studies reflect a trend similar to that in the U.S. In Canada, autism prevalence grew from 0.12% for birth years 1987-1991, to 2.16% in a study concerning birth year 2006.

In Denmark, children born in about 1980 had a .01% autism prevalence, but a more recent study from 2018 found a 2.8% rate. A 2015 study finding an increase in autism back in the very earliest years of the autism surge, births 1980-1991, found that a change in diagnostic criteria in 1994 and the inclusion of outpatient diagnoses in 1995 (specific to Denmark) accounted for perhaps 40% of increase over that specific period of time. There’s no indication in more recent rates, including the 2.8% in the 2018 study, are owing to diagnostic shifts. Consistently higher autism rates in each birth cohort from 1990 to 2007 were seen not just in Denmark but also in Sweden, Finland and Western Australia. In Iceland, children born between 1994 and 1998 and followed until 2009, had an autism prevalence of 1.2%, but children born approximately 2006-2008 had a sharply higher prevalence of 3.13%.

Israel has the advantage of massive nation-wide health and benefits insurance databases which epidemiologists have used to track prevalence over time. Most recently, Dinstein et al. 2024 reported a rate of 1.56% for children born in 2013. This is a large increase from estimates of 0.3% in 2008, 0.65% in 2015 and 1.3% in 2018. A 2015 study on the cumulative incidence of ASD child disability benefits in Israel, at age 8, for birth years 1992 to 2003, shows a skyrocketing increase in autism disability claims versus modest growth for other disabilities. A 2020 study by Davidovitch et al., finding the unprecedented 1.8% rate, stated that “changes affecting diagnostic criteria for ASD and eligibility for ASD-related services did not appreciably affect these trends.”

Japan has also witnessed climbing autism rates. For children born in 1988, prevalence was 0.21%, with about half of children having IQs of 70 and above. In more recent years, the cumulative incidence for each birth cohort showed a steady increase in autism, from 2.23% for the 2009 birth cohort to 3.26% for the 2014 birth cohort.

Interestingly, lower autism rates have been detected outside of industrialized countries. For example, a study of children in rural Nepal 2001-2004 yielded 0.3%, and 1.11% for children in parts of India born 2000-2010.

Arguments against a true increase

Change of coding systems. While people often invoke changes in coding systems as a factor driving increasing rates of diagnosis, a large study found a shift to the ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision), which the U.S. adopted in 2015, did not meaningfully affect autism rates at ten large healthcare systems. The rates of autism were increasing for 0- to 5-year-olds before the transition to the ICD-10 and did not substantively change after the new coding was in place. Similarly, in South Korea, changing from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM-IV to DSM-V led to a decrease in autism prevalence. An intensive community case-finding study found 2.64% childhood ASD prevalence under DSM-IV. The number decreased by 17% to 2.2% under DSM-V.

Studies. Proponents of the no-increase hypothesis often trot out a smattering of studies to support the idea that autism has always been here at today’s high rates. Let’s look at some.

A 2011 paper and 2016 report by Traolach Brugha, a professor at the University of Leicester, England are often invoked to counter the evidence for rising prevalence. The 2011 paper looked for autism in persons aged 16 and older residing in a small area of England, around the University, using a convoluted experimental self-report methodology and not gold-standard case ascertainment. The study concluded an autism prevalence of 1% for age 16 and older, based on just 19 cases.

The 2016 Report also came with a disclaimer: “Statistics relating to autism in this report are experimental” with methods “validated” only by Brugha and his team. The report estimated prevalence of adult autism at 0.8%, with a wide confidence interval. This was based on just 31 cases from combined 2007 and 2014 samples. Even the report noted it was “small for subgroup analysis and means caution with interpretation is required.” It also had red-flag questionable findings, such as: “Among 16 to 64 year olds, employment status was not significantly related to whether or not someone was identified with autism.” This is odd because it’s well established that adults with autism have poor employment outcomes relative to typically developing individuals.

Needless to say, even putting aside the questionable methodology, the 1% or 0.8% prevalence found is far lower than the nearly 3% prevalence reported in children. Most risibly, even Brugha’s 2016 report found increasing birth year prevalence, with much higher rates in the 16-34 bracket than those 35 and older [Figure 16]. Even his own work confirmed a longitudinal increase in autism prevalence. As an aside, I can recall attending a session at the International Society for Autism Research meeting in Austin, Texas in 2022, when Dr. John Constantino, then of Washington University, refuted a question about growing rates of autism by pointing to the Brugha work, saying the question “has been asked and answered.” Horrified by his superficial reading of the reports, my jaw dropped to the floor but pretty much everyone else in the room nodded in agreement.

Related to the Brugha brouhaha, a frequently cited Nature Reviews Disease Primer published in 2020, viewed as a definitive consensus statement about autism, contained a brief section about autism prevalence authored by Dr. Brugha (per email to me from lead author Dr. Cathy Lord). It denies an increase in autism, stating there is “no clear evidence of a change in the prevalence of autism in the community between 1990 and 2010.” Of the six very cherry-picked studies cited for this proposition, three are to work by Brugha himself, and the other three studies offered no data to support the assertion of no increase. Nevertheless this sloppy and biased paragraph in a leading journal is sometimes construed as a sort of proof that autism prevalence has not increased. In reality it is scientific malpractice.

Another paper often cited is by Polyak et al. 2015, for the idea that autism’s increase was only caused by diagnostic shifts away from ID to ASD. The paper was not an epidemiological study on autism increase over time but instead intended to look for hints of common molecular origin for comorbid conditions. It was conducted by geneticists, not epidemiologists using proper tools of that trade. Instead of focusing on birth year prevalence, this study performed a clumping of all ages 3-21, which is meaningless to determine autism rates over time. It ended with a 0.52% autism prevalence in 2010 (a meaningless number because it's not based on birth year, as one sees with CDC ADDM for example). In any event, the study found that a large percent of the autism increase was not accounted for by declining ID, and many states did not reflect this trend at all, including the most populous states, California and Texas. Furthermore, the data is now 14 years old, and autism rates have clearly continued surging over that time. Moreover, the federal Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) shows a dramatic increase in autism in special eduction, to 909,055 in 2022-23, up from 513,688 in 2014-15. Meanwhile OSEP data shows ID cases have flatlined, not decreased, 420,000 in 2022-23 from 415,335 in 2014-15.

A 2006 paper by Paul Shattuck is also often invoked for the argument that diagnostic substitution explains the increase in autism. Shattuck examined the administrative prevalence of autism among children ages 6-11 in US special education from 1994 to 2003 (corresponding to birth years 1983-1988 for ascertainment in 1994, to birth years 1992-1997 for ascertainment in 2003), finding higher autism prevalence was significantly associated with corresponding declines in the prevalence of mental retardation and learning disabilities. First and most obviously, this data is very old by autism history standards, and in large part pre-dates the tsunami of autism cases. The average administrative prevalence of autism among 6-11 year old children increased from 0.06% to 0.31% from 1994 to 2003. These rates are minuscule compared to the 3% rates seen widely in special education today. The Shattuck data say nothing about the surge that accelerated after birth year 1997. In addition, there may be other reasons for declining prevalence of mental retardation and learning disabilities from 1994 to 2003, including pregnancy terminations and improved prenatal care. Also, the most populous state, California, was among several that did not see the increase in autism correspond to a decline in other categories. And as I demonstrated above, the more recent data show ASD cases exploded while intellectual disability remained flat.

A recent and sadly oft-cited U.S. study that attempted to ascertain adult prevalence was conducted only as a modeling experiment, led by the CDC. This paper however, did nothing more than take current childhood rates and project them onto older ages, without attempting a single stab at actual case-finding. This woefully superficial analysis is clearly lethally infected by a flawed, baseless set of assumptions about autism prevalence being steady over time, and must be, in my view, one of the most misleading papers in the history of autism.

A similarly dubious approach was taken in England by O’Nions et al. Their 2023 paper found rates of diagnosed autism in children/young people were much higher than in adults/older adults. As of 2018, 2.94% of 10- to 14-year-olds (born approx 2004-2008) had a diagnosis (1 in 34), vs. 0.02% aged 70+ (1 in 6,000). That’s a 147-fold increase. Then the researchers took an enormous leap of faith. They assumed a constant birth year prevalence over the decades to suggest that the data means that between 435,700 and 1,197,300 people in England may be autistic and undiagnosed. A ludicrous assumption with an equally ludicrous result.

Conclusion

We often hear that the autism increase is a mere artifact of changing conceptualizations but the data do not support that idea. The reasons people deny a reality of an autism epidemic are not scientific in nature but rather sociological.

First, with all good intentions both researchers and the media were hyper-cautious in reporting rising autism rates to defend against the debunked and dangerous hypothesis that childhood vaccinations cause autism. Second, with the strong evidence of autism’s heritability grew a rigid dogma that autism must be genetic in origin, and therefore could not be increasingly common. Though heritability may indeed be environmental in origin (this is the focus of my work as a research philanthropist), the faulty dogma has grown so strong that it cast a pall over all of epidemiology. Autism genetics seems to be a field that is impervious to negative feedback, but I believe that in the coming years the door will open to new ideas about autism’s origins and heritability.

Third, the rise of the neurodiversity ideology rested on some magical thinking that autism is more of a difference than a disorder, and saw autism more as an identify than a set of neurodevelopmental deficits. Adherents of this ideology simply could not accept that idea that autism rates were growing, a phenomenon seen in the popular revisionist history of autism by Steve Silberman, NeuroTribes (2015).

And as horrible as the autism surge might seem, the situation on the ground is actually far more dire than what I’ve so far presented. The skyrocketing autism rates are just one part of a larger picture of mysteriously perturbed brain wiring in children in recent decades, as we see concurrent, if perplexing, surges in ADHD and other mental disorders like anxiety, depression, and gender dysphoria, all of which are alarming in themselves.

We can try to theorize it away, to obscure and downplay reality. We can try to rebrand the autism epidemic as an epidemic of awareness while wishful thinking rushes into fill an explanatory void. But mental gymnastics simply cannot explain the increase. We normalize at our peril this national emergency of obscene, unexplained rates of abnormal neurodevelopment.

Post Script (December 13, 2024)

Pursuant to a Public Records Act request to the California Department of Developmental Services, I received updated data on Autism Disorder cases in the CalDDS system, by birth year (as of November 2024). Here is a graph of the cases for birth years 1947-2019, below. It is hard for me to fathom how anyone could possibly attribute this stupendous growth to “awareness” when there is clearly no evidence for system influx of adults and while the system has grown increasingly restrictive about eligibility requirements.

Jill Escher is an autism research philanthropist (EscherFund.org), president of National Council on Severe Autism (ncsautism.org), past president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area (sfautismsociety.org) and that mother of two children with idiopathic profound autism. More info at jillescher.com.