By Jill Escher

INSAR had one attendee with profound autism, my daughter Sophie.

Last week I attended the world's biggest annual autism research conference, held by the International Society for Autism Research (INSAR). Several of us from NCSA flew to Austin, Texas for the 1000+ person conference, along with the one attendee with profound autism, my delightful nonverbal autistic daughter Sophie. To be fair, she was in tow not because she longed to attend sessions such as "Chromatin and Gene-Regulatory Dynamics of the Developing Human Cerebral Cortex,” but to hang with her very beloved oldest bro, who lives there.

This conference was massive, with hundreds of presentations and posters over 3ish days; one could only absorb a small fraction. So while my comments here hardly reflect the conference as a whole, I'd thought I'd share some high- and low-lights I encountered along the way:

Lowlight: Neurodiversity love-fest. Severe autism, not so much.

In recent years, INSAR has taken a sharp turn in favor of neurodiversity themes. Super high-functioning autistic adults were often included as panel speakers, including John Elder Robison, Alex Plank, and James Cusak of the UK org Autistica, but apparently parent advocates speaking on behalf of the severely affected were not quite so worthy. We saw many researchers invoking the importance of including "Autistic voices" in research yet I heard not one emphasizing the need for including autism parents speaking out for the most seriously impaired who cannot speak for themselves. I was hardly the only one to notice this bias, which had many clinicians and researchers rolling their eyes at the virtue-signalling spectacle that too often begrudged a vast portion of the autism population.

While the stupendous increase in autism was broadly acknowledged, INSAR hit a low when Mr. Plank’s presentation insisted that autism is “clearly not an epidemic, clearly it is not.” Evidence much, Alex? Why would INSAR platform stakeholders who embrace pseudoscience?

Sessions often foregrounded milder forms of autism to the exclusion of autism with intellectual disability. For example, if a session title included terms like “Autistic Adults,” “Autistic Individuals,” “Autistic People,” “Autistic Flourishing” (yes, that was a thing), or “Autistic Youth” you could be fairly sure they didn’t mean “Autistic” at all, but only the high end of the spectrum.

From time to time neurodiversity advocates complained about “ableism” (hey, guess what? autism research is about reducing and preventing disability, I know that is shocking!) and tried to neuter the vocabulary of autism. One complained openly about a presenter’s use of “ASD” (because it includes the word “disorder”) insisting only the term “autism” should be allowed because it was “neutral.” Seriously? As countless tens of thousands of you and your children/adults were suffering immeasurably at home, dealing with broken furniture, lost jobs, tattered marriages, a broken system without adult programs, years-long waitlists, fecal smearing, impoverishment, bruises, ER visits, medication trials, inability to find practitioners even a babysitter, hopelessness about future, and worse, an advocate with no discernible traits of autism tells us not to consider autism a disorder. It sometimes felt like a parody of the excesses of the neurodiversity movement.

At a group lunch after these sessions, one attendee suggested to us a new word to apply to all those who don’t feel their autism is a disorder: let’s call their version of autism “schmautism” instead, she said. #Truth

Highlight: A nod to our care system failure

“An urgent public health phenomenon” is putting it gently (my annotation).

On another positive note, I saw widespread acknowledgment that our care systems are failing people disabled by autism. Our hospital, ER, longer-term care, reimbursement, and Medicaid systems were all designed long before the meteoric increase in autism cases. These systems are now heavily (and unexpectedly) burdened by autism but sorely ill-equipped to respond. We need better treatment guidelines guided by practical clinical research, and vastly more services in communities, many speakers emphasized. And, as Dr. Charman noted, “We need better information, counting, to inform the case for government and societal investment and support worldwide.” Alarming data from New Jersey pointed to the urgent need to expand services for the rapidly increasing autism population.

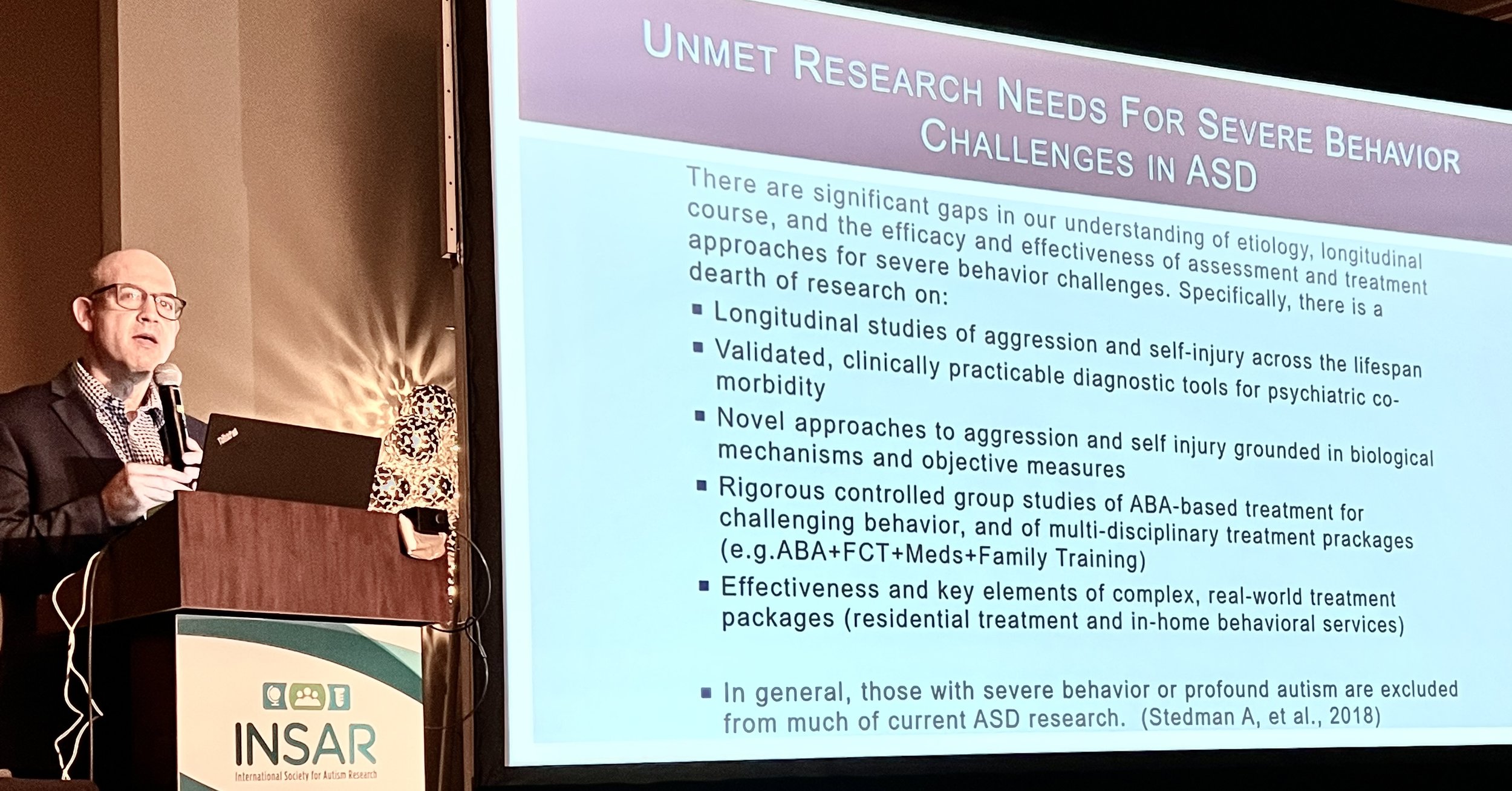

Highlight: A special interest group on severe behaviors

Dr. Matthew Siegel presenting at the SIG on severe behaviors.

Of course, one highlight was the Special Interest Group (SIG) sponsored by NCSA about the treatment for severe and challenging behaviors in profound autism. Yes I am biased, but this 7am group was truly excellent and, unlike 99% of sessions, hammered on questions of extreme urgency for severe autism families. Chaired by Lee Wachtel, MD, and Imtiaz Mubbasshar, MD of Kennedy Krieger Institute, the other speakers included Matt Siegel, MD, of Maine Behavioral Health, Deborah Bilder, MD, of University of Utah, Nathan Call, PhD of Emory, Henry Roane, PhD, of Upstate Medical University, Alycia Halladay, PhD of Autism Science Foundation, Donna Murray, PhD of Autism Speaks, and more. Severe behaviors can be ruinous to quality of life, and families are desperate to reduce aggression, self-injury, pica and property destruction, and the like, but the options are few and the research is thin. I was shocked when Dr. Siegel quoted a staffer at the NIH (the source of most autism research funding in the U.S.) as saying "Haven't we already done that?” in dismissing calls for ongoing work in this area. In other words the NIH seems detached from one of the most nightmarish public health crises of our time. People, the ignorance is real.

Our SIG goal is to have tangible, meaningful next steps to energize this field forward. We will post updates (and slides) soon.

Highlight: Does the autism emperor have no clothes?

A keynote by Evdokia Anagnostou, MD, a pediatric neurologist of the University of Toronto, presented her group’s research suggesting that while the DSM construct of ASD may be convenient, it does not reflect actual brain biology, and that characterizing mental health disorders/seizures/sleep dysfunction/seizures/etc as "co-occuring conditions" may not be scientifically honest or fair to patients. Symptoms that “co-occur” are likely varying manifestations of unnamed original neurodevelopmental pathologies (applause!). Most kids with ASD have a wide variety of diagnoses and labels that are in reality inextricably intertwined; they are not a menu of dysfunctions that converge on a patient “by chance.”

Dr. Anagnostou

To investigate what’s really underneath autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders, she and her colleagues developed a “zero hypothesis model” that examined brains and functioning of children with ASD, ADHD, and other conditions. They found high genomic variability (though only 10% had genetic diagnosis), but nothing in particular to autism when comparing to other neurodevelopmental disorders. They saw no genetic defects were specific for autism. This was a theme expressed in other sessions as well, for example by David Skuse, MD of University College London showing data reflecting that “There are no autism specific genes, just brain genes.”

In a study based on brain imaging, the team found differences among the children’s brains — but based on their level of adaptive function and not their diagnosis (eg, ASD v ADHD). Nothing about so-called “autism” was particularly distinct. Another study saw a similar finding — brain function differences depended mainly on IQ, and not an ASD diagnosis (more applause!). As Alycia Halladay, PhD of the Autism Science Foundation summed it up, “brain biology does not track with diagnostic labels like ASD, ADHD, etc, but is DOES track with differences in cognition and adaptive function.”

Although preliminary, Dr. Anagnostou’s studies suggested that today’s diagnostic labels do not help us clarify the reality of the highly heterogeneous patient population, a heterogeneity rooted in complex biology. She invoked the recent Lancet Commission report to emphasize the importance of constructing diagnosis and treatment in ways that actually make life better for patients. “Otherwise,” she said “It’s just an intellectual exercise.”

Another thing to love about her presentation was her discussion of “autism traits” vs. “autism” as a diagnosis and disorder. While she acknowledged those who see autism as an identity or even strength, she explained that “distress and impairment” bring people to her clinic, and not merely “traits in general population.” She said these two kinds of autism require “a different ethical framework.” We need “the construct of deficit-based pathology” for the profession to help people who are suffering reach their goals: “That’s what people come to me for.” While she acknowledged that a strength profile could inform better therapeutic decisions, mere “diversity is not what docs should be doing.” (Hurrah!)

I should note that Dr. Charman relayed similar sentiments earlier in the Lancet panel, saying “clinical practice is not about phenomenology, it’s not just about being different. The term profound autism, to which some neurodiversity advocates object, “has a meaning and relevance” about the individuals and their need for care and improved outcomes. “The term captures something important about a wide range of individuals,” he said, “clearly the term has utility.”

Highlight: Autism brains — abnormal, not just “diverse”

In the neuroscience sessions we saw increasing evidence that differences in brain structure (and microstructure) likely underpin different phenotypes. Studies noted decreased brain connectivity, reduced thickness of the cerebral cortex, and abnormalities in the subcortical structures as well. Different types of neurons were seen to be reduced in subjects with ASD, for example throughout prefrontal cortex. Autism brains were not just “diverse” — but harbored neurological pathology linked to behavioral and learning impairment. No, autism is not “neurodiversity,” it’s serious dysfunction rooted in biological abnormality. Why these defects occur is still largely unknown except in the case of some rare genetic disorders.

Lowlight: In genetics, doubling down on failed strategies

Autism is a strongly heritable condition, owing mainly to high recurrence rates among twins and siblings. But despite enormous research in genetics we see that very little of this heritability stems from genetic mutation, with only a tiny portion of cases resulting from inherited mutation (most are de novo, or newly occurring). Despite grandiose statements that “autism is genetic,” the evidence is overwhelming that autism is heritable, yes, but by and large not in fact genetic.

So that leaves a question, where do we hunt for the missing heritability of autism? While I have argued (including in major scientific journals such as here) that we should turn our attention to the question of non-genetic inheritance (resulting from exposures to parents’ germ cells), geneticists seem intent on doubling down on their same failed DNA-sequencing strategies. To my mind, this is a disastrous waste of precious research dollars and betrayal of common sense and public health. Autism research sometimes seems to become a navel-gazing grant-seeking sport with little curiosity about new ideas and hypotheses, and we are all left, year after year, without meaningful answers about what causes autism and why it has increased so astronomically.

Last note

Finally, I hope those fortunate enough to attend INSAR recognize their immense privilege in being so free from responsibility to care for children and adults with autism that they were able to attend, and so cognitively and behaviorally intact that they could travel to Austin and understand the presentations. Most of the autism community has no such luck.

Jill Escher is President of NCSA.

Disclaimer: Blogposts on the NCSA blog represent the opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily the views or positions of the NCSA or its board of directors. Inclusion of any product or service in a blogpost is not an advertisement, is not made for any compensation, and does not represent an official endorsement.