A major new review, with a stamp of approval from Autism Speaks, denies any increase in autism. The autism community should be aghast at the incompetence.

By Jill Escher

In spite of overwhelming evidence of skyrocketing autism rates, a coterie of autism researchers just announced in a key and influential publication that there has been no actual increase in autism.

Nature is the crème de la crème of scientific journals. It is also an umbrella, publishing many other journals, including one called Nature Reviews Disease Primers (NRDP). These primers are highly respected in the scientific and medical fields and are often cited as gold-standard authority regarding a variety of diseases and disorders.

Cathy Lord, PhD, left, was lead author of a major review contending there has been no true increase in autism. Traolach Brugha, MD, middle, penned the section. Tom Frazier, MD, Chief Science Officer of Autism Speaks, right, was among those who signed off.

In January of this year, lead author Cathy Lord, PhD, and co-authors published the NRDP Primer on autism spectrum disorder (1). This Primer will be cited as reliable authority for years to come on many issues related to autism. It has a lot of outstanding content and I would actually recommend 90% of it.

But then, there’s the crackpot part denying that autism rates have increased.

The paragraph acknowledges that “Many individuals and groups presume that rates of autism are increasing over time” (well, yeah), but then goes on to deny any evidence of a true increase, saying flatly that studies have “confirmed the lack of significant change in prevalence rates” over time.

Say what? On what planet?

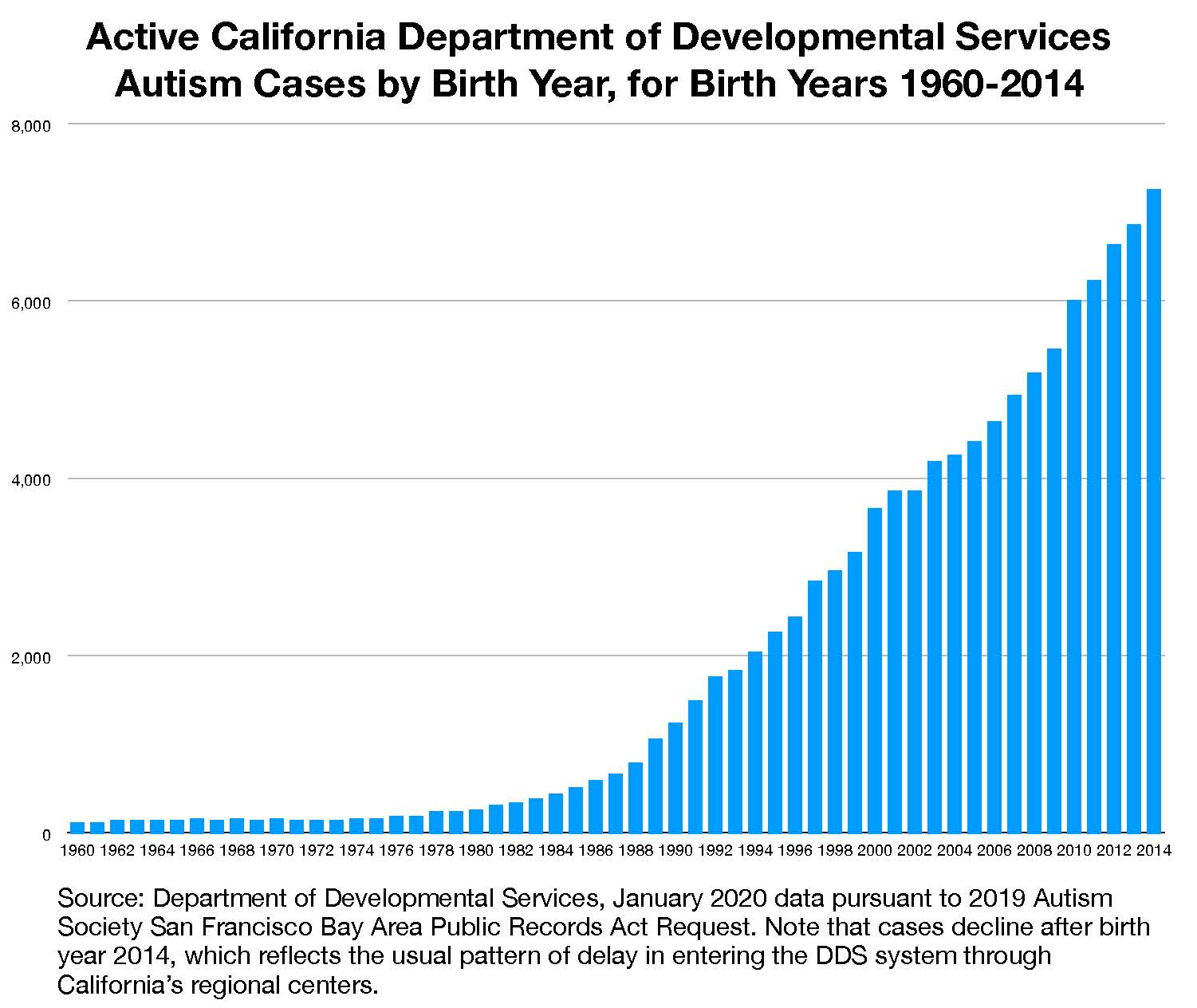

Because actual data from planet Earth paints a cataclysmic picture. The latest report from the California Department of Developmental Services, for example, indicates its autism caseload (which is limited to developmental disability-level autism) has grown 4,000% from 1989 to 2020: from about 3,000 cases to about 126,000 (2), an eye-popping number far exceeding prior increases (3, 4). Heck, in my County of Santa Clara alone, DDS-eligible autism has soared from 147 cases in 1990 (5) to 4,505 today (2). These California data compare apples to apples, relying as they do on objective measures of mental and adaptive functioning. Though some small amount may relate to diagnostic shifts (4), eligibility criteria narrowed in 2003 and have not broadened to encompass milder cases.

Autism cases sufficiently severe to be included in California’s developmental disability system have skyrocketed, vastly outstripping population growth, from a few hundred births per year in the early 1980s to more than 7,200 births per year in 2014. For a recent prevalence analysis by the California Department of Public Health, see here.

And of course, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control has famously found steady increases in childhood prevalence, from 1 in 150 in 2000 to 1 in 54 in 2016 (6, 7), including an unprecedented 3% rate among New Jersey children (7, 8). A study in Atlanta found ID and CP rates fairly stable from 1996–2010, but ASD average annual prevalence increased 9.3% per year. The prevalence of ASD both with and without co-occurring ID increased (9), a trend widely seen in the literature (for example 6, 7, 11).

Outside the U.S., we’ve seen similar trends. In three regions of Canada, the estimated average annual percent increases in prevalence among children 2–14 years of age ranged from 9.7% to 14.6%. “[W]e cannot rule out the possibility of a true increase in incidence,” said the researchers (10). The prevalence of ASD in Western Australia was seen to increase by 11.9% per year, from 8 cases per 10,000 births in 1983 to 46 cases per 10,000 births in 1999. A rise in all types of ASD was seen and a “true increase in ASD cannot be ruled out,” said the authors (11).

Finland saw an eight-fold increase in the incidence rates in children of diagnosed ASD born between 1987 and 1992 (12). In Israel, prevalence data indicated an increase from 1.2 per 1,000 in those born in 1986 to 3.6 per 1,000 in 2003 (13). A new report from Northern Ireland showed an increase from 1.2% in 2008 to 4.2% in 2019 of children identified with autism. Among boys, the prevalence was the stuff of nightmares, about 6.4% (14). Again, most studies that look find increases across all levels of autism. Moreover, this phenomenon of increasing prevalence is seen in many childhood neuropsychiatric disorders, not limited to ASD (for example, 15).

And that’s just a sampling of hundreds of such reports and studies. So what gives with the Primer? While it indicates that “All authors read and edited the full document,” it also says the epidemiology section was penned by Traolach S. Brugha, MD, an adult psychiatrist at University of Leicester, U.K., who has been an outspoken increase denier.

“The vast majority of epidemiological literature was simply ignored.”

Of the six papers cited in the Primer’s paragraph contending there has been no increase in autism (anywhere in the world, it seems), four were to Brugha’s own work, and none supported the claim. The vast majority of epidemiological literature was simply ignored.

Of the Brugha papers, one was irrelevant to the question (16). Another, a U.K. administrative report on various mental disorders, was based on a minuscule sample, acknowledged its own methodological shortcomings and stated, contrary to the Primer, that one cannot “rule out the possibility that the prevalence of ASD has increased” (17). The third suggested a .98% rate of suspected autism in a sample of people aged 16 and up in England (18), using experimental methods. Even if true, this rate falls far short of the nearly 2% rate now seen among U.S. children. Not to mention the 2.64% rate among Korean children (19), the 3% rate in New Jersey, or the 4.2% rate in Northern Ireland.

The Global Burden of Disease study (20), to which Brugha contributed, which surveyed 354 diseases, and on which the no-increase argument primarily relies, is so opaque one cannot ascertain the methodologies used, and was clearly not intended to show changes in autism prevalence over time in any identified regions or countries. The other U.K. report (21) found increasing autism rates among younger cohorts of children, again contradicting the assertion of no increase. Finally, a study on Swedish children (22) did not ascertain prevalence changes, but rather behavioral characteristics that are related to autism, over a constrained period of time. Indeed, a recent study in neighboring Denmark saw no sign of a plateau in increasing autism prevalence (23).

So why would Autism Speaks' Chief Science Officer Tom Frazier, MD (not to mention other co-authors) have signed off on a section so cherry-picked and extravagantly misleading? I mean, how much higher do the ASD numbers have to be before the Ivory Tower sounds an alarm? Five percent of children? Ten? Armageddon? Perhaps Dr. Frazier — who is one of the nicest people I know, I should clarify — was unwilling to counter a colleague, was too busy to notice, or assented in a noble effort to help quell anti-vaccine sentiment.

“Just because we’ve identified few of autism’s causes does not justify fabricating a false narrative of no increase.”

This motive, if true, has my sympathy, but the debunked vaccine theory has no bearing on the reality of the unrelenting ascent of serious, permanent brain dysfunction in our children. Just because we’ve identified few of autism’s causes does not justify fabricating a false narrative of no increase.

This is no obscure academic dispute. This Primer will be used by researchers, policymakers and media as authority for the proposition there has been no growth in autism. No crisis to address. No reason to seek non-genetic causes or pursue prevention. No reason to panic about our flood of dependent, mentally and functionally incapacitated adults biting the furniture and needing 24/7 care. Hey, autism’s always been here in these numbers, Maybe We Called It Something Else (though records are devoid such evidence), so Calm Down, Celebrate “Neurodiversity,” and Go Away.

Autism’s increase — particularly the scorching surge in severe disability — is an urgent, foundational fact that should drive public communications, policy and research. But here a cloak is thrown over the truth. We in the autism community have been betrayed, and will be paying for this act of scientific misconduct for many years to come.

Jill Escher is president of National Council on Severe Autism, and founder of Escher Fund for Autism, which promotes research in non-genetic inheritance in autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, she is the mother of two children with idiopathic nonverbal forms of autism.

Related posts by Jill Escher:

CDC Study Estimates 2.2% of U.S. Adults Have Autism — Don’t Believe a Word of It (2020)

The torrential surge in autism continues unabated (2020)

1 in 54: Autism's Continuing Climb, with Dr. Walter Zahorodny (2020)

What the autism needs now is truth, sweet truth (2019)

‘Denial’: Serving Up Devastating Autism Truth With a Side of Dumdum (2019)

NeuroTribes: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back for Autism (2016)

References

(1) Lord C et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 6:5 (2020). Paywalled at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-019-0138-4.

(2) State of California Department of Developmental Services. Quarterly Consumer Characteristics Report Index for the end of March 2020 (2020) (latest figure at nearly 126,000). The 3,000 caseload figure from 1989 is also from DDS data, see https://www.sfautismsociety.org/uploads/1/1/7/4/11747519/autism_rising_2015.pdf (2015).

(3) Nevison C et al. California Autism Prevalence Trends from 1931 to 2014 and Comparison to National ASD Data from IDEA and ADDM. J Autism Dev Disord. 48, 4103–4117 (2018) (prevalence of autism in the California Department of Developmental Services increased from 0.001% in the cohort born in 1931 to 1.2% among 5 year-olds born in 2012).

(4) Hertz-Picciotto I et al. The Rise in Autism and the Role of Age at Diagnosis. Epidemiology. 20(1), 84–90 (2009) (the incidence of autism rose 7- to 8-fold in California from the early 1990s through 2006. Changes in diagnostic criteria cannot fully explain the magnitude of the rise in autism).

(5) Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area, Autism by The Numbers, data from California Department of Developmental Services. Retrieved from https://www.sfautismsociety.org/sf-bay-area-autism-by-numbers.html.

(6) U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Website https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

(7) Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, Washington A, Patrick M, DiRienzo M, Christensen DL, Wiggins LD, Pettygrove S, Andrews JG, et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 69:4;1–12 (2020).

(8) U.S. Centers for Disease Control. A Snapshot of Autism Spectrum Disorder in New Jersey (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm-community-report/new-jersey.html

(9) Van Naarden Braun K et al. Trends in the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cerebral Palsy, Hearing Loss, Intellectual Disability, and Vision Impairment, Metropolitan Atlanta, 1991–2010. PLoS One. 2015; 10(4): e0124120 (2015).

(10) Ouellette-Kuntz H et al. The changing prevalence of autism in three regions of Canada. J Autism Dev Disord. 44, 120–136 (2014).

(11) Nassar N et al. Autism spectrum disorders in young children: effect of changes in diagnostic practices. Int J Epidemiol. 38(5), 1245–1254 (2009).

(12) Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S. The incidence of diagnosed autism spectrum disorders in Finland. Nord J Psychiatry. 68, 472-480 (2014).

(13) Gal G et al. Time Trends in Reported Autism Spectrum Disorders in Israel, 1986–2005. J Autism Dev Disord. 42, 428–431 (2012).

(14) Rodgers H et al. The prevalence of autism (including Asperger syndrome) in school age children in Northern Ireland 2020. (2020) Retrieved from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/prevalence-autism-including-aspergers-syndrome-school-age-children-northern-ireland-2020.

(15) Atladottir HO et a. The increasing prevalence of reported diagnoses of childhood psychiatric disorders: a descriptive multinational comparison. Eur Child & Adolescent Psych. 24;173–183 (2015).

(16) Tromans S et al. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in adult psychiatric inpatients: a systematic review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 14, 177–187 (2018).

(17) Brugha TS et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder, in McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T. (eds.) Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital (2016). Retrieved from https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1518055/1/APMS%202014-full-rpt.pdf. (Based on “experimental statistics,” prevalence of adult autism estimated to be .8%, with a wide confidence interval, based on … 31 cases. Note that Brugha is content to cite to a report on 31 cases, while ignoring California data, now including 125,000 developmental disability level autism cases.)

(18) Brugha TS et al. Epidemiology of autism in adults across age groups and ability levels. Br. J. Psychiatry 209, 498–503 (2016).

(19) Kim YS et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders in a Total Population Sample. Am J Psychiatry. 9, 904-912 (2011).

(20) GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

(21) Marcheselli F et al. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017. NHS https://digital. nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/ mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-inengland/2017/2017 (2018).

(22) Lundstrom S et al. Autism phenotype versus registered diagnosis in Swedish children: prevalence trends over 10 years in general population samples. BMJ 350, h1961 (2015).

(23) Schendel DE et al. Cumulative Incidence of Autism Into Adulthood for Birth Cohorts in Denmark, 1980-2012. JAMA. 320(17):1811-1813 (2018).

Appendix 1: Full list of NRDP Autism Spectrum Disorder authors

Catherine Lord1*, Traolach S. Brugha2, Tony Charman3, James Cusack4, Guillaume Dumas5, Thomas Frazier6, Emily J. H. Jones7, Rebecca M. Jones8,9, Andrew Pickles3, Matthew W. State10, Julie Lounds Taylor11 and Jeremy Veenstra VanderWeele12

1 Departments of Psychiatry and School of Education, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

2 Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

3 Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK.

4 Autistica, London, UK.

5 Institut Pasteur, UMR3571 CNRS, Université de Paris, Paris, France.

6 Autism Speaks, New York, NY, USA.

7 Centre for Brain & Cognitive Development, University of London, London, UK.

8 The Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology, New York, NY, USA.

9 The Center for Autism and the Developing Brain, White Plains, NY, USA.

10 Department of Psychiatry, Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute and Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

11 Department of Pediatrics and Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

12 Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Appendix 2: The paragraph of the Primer (paywalled) discussed in this blogpost

Many individuals and groups presume that rates of

autism are increasing over time, but this supposition is

based on data from administrative records rather than

community-based studies. Indeed, after accounting for

methodological variations between studies, there was no

clear evidence of a change in the prevalence of autism in

the community between 1990 and 2010 (ref.13). In addition,

general population and systematic case-finding

community-based surveys (including testing of representative

populations) have also confirmed the lack of

significant change in prevalence rates in childhood14 and

adulthood15 over time. No significant evidence is available

supporting that autism is rarer in older people, which

provides further evidence against the suggestion that

autism is increasing in prevalence over time4. Even in

high-income countries with strong autism public health

policies, there is evidence that autism in adults goes

largely unrecognized, whereas administratively recorded

diagnoses in children increase year by year16. This finding

highlights the importance of obtaining information

on autism rates in settings where professionals may be

able to improve its recognition. The prevalence of autism

in mental health inpatient settings is estimated to be

far higher than in the general population, ranging from

4% to 9.9%17.

(Refs as cited in the paper)

4. Brugha, T. S. et al. Epidemiology of autism in adults

across age groups and ability levels. Br. J. Psychiatry

209, 498–503 (2016).

This paper uses active case-finding to provide

representative estimates of the prevalence of

autism and demonstrated that rates of autism in

men and women are equivalent in adults with

moderate-to-profound intellectual disability.

13. GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and

Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and

national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with

disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195

countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic

analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

14. Marcheselli, F. et al. Mental health of children and

young people in England, 2017. NHS https://digital.

nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/

mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-inengland/

2017/2017 (2018).

15. Brugha, T. C. et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder,

Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. (2014).

16. Lundstrom, S., Reichenberg, A., Anckarsater, H.,

Lichtenstein, P. & Gillberg, C. Autism phenotype

versus registered diagnosis in Swedish children:

prevalence trends over 10 years in general population

samples. BMJ 350, h1961 (2015).

17. Tromans, S., Chester, V., Kiani, R., Alexander, R.

& Brugha, T. The prevalence of autism spectrum

disorders in adult psychiatric inpatients: a systematic

review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 14,

177–187 (2018).

Disclaimer: Blogposts on the NCSA blog represent the opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily the views or positions of the NCSA or its board of directors.