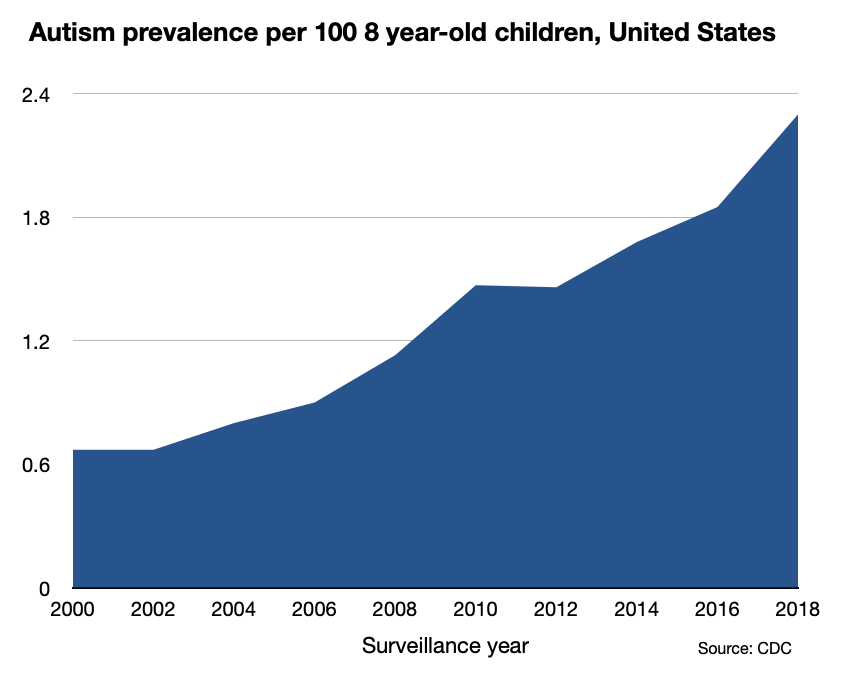

Birth year autism rates among American children have tripled over the past 18 years — a phenomenon that cannot be explained by broadening diagnostics.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control has issued alarming new data indicating that the rate of autism among U.S. 8 year-old children has risen again, this time to 1 in 44, or about 2.3%.

The report comes from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, which conducts active surveillance of ASD. The children under study were aged 8 years in 2018 (born in 2010) and whose parents or guardians lived in 11 ADDM Network sites in the United States (certain regions within Arizona, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin).

The new numbers represent a dramatic increase over 18 years — more than triple the autism prevalence found in the CDC’s year 2000 surveillance. The 2000 study found ASD birth-year prevalence of 1 in 150 8 year-olds, or .67% — which at the time was considerably higher than previous findings. Robust studies of children born in the 1960s found a national autism rate of .046%, indicating a 50-fold increase to today’s childhood autism numbers.

To arrive at the new 2.3% rate, ADDM staff reviewed and abstracted developmental evaluations and records from medical providers and schools. Among the 5,058 children who met the ASD case definition, 75.8% had a diagnostic statement of ASD in an evaluation, 18.8% had an ASD special education classification or eligibility and no ASD diagnostic statement, and 5.4% had an ASD ICD code only.

ASD prevalence among the study sites ranged widely, from 1.65% in Missouri to nearly 4% in the California site, based in a metropolitan area of San Diego. Consistent with previous studies, ASD was 4.2 times as prevalent among boys as among girls. Overall ASD prevalence was similar across racial and ethnic groups, except American Indian/Alaska Native children had higher ASD prevalence than White children. At multiple sites, Hispanic children had lower ASD prevalence than White and Black children.

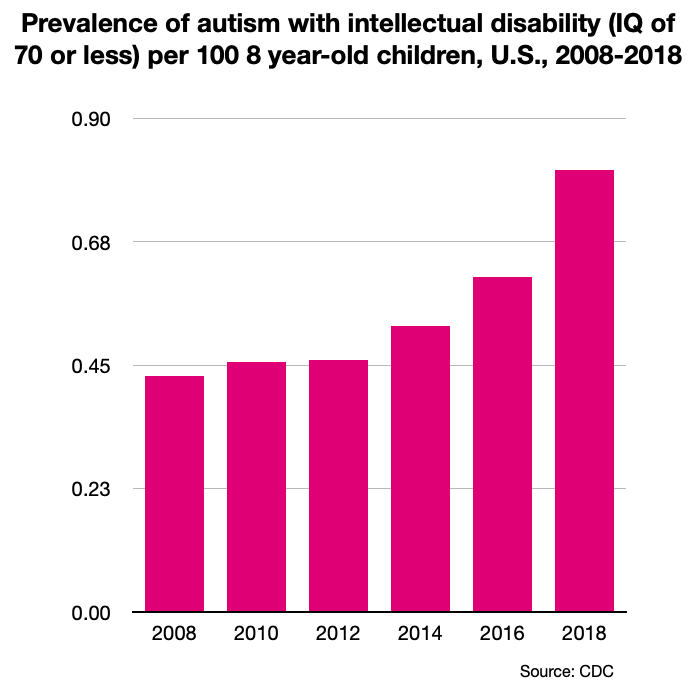

It is often suggested that steadily climbing autism rates are merely a result of broadening diagnostic criteria over time to include persons who are more mildly affected and lack intellectual disability. However, the ADDM data indicate that ASD rates are climbing among all groups based on cognitive ability.

Among the 3,007 children with ASD and data on cognitive ability in the present cohort,

• 35% had intellectual disability (ID) (IQ of 70 or under) — up from 33% two years prior and 31% four years prior

• 23% had borderline ID (IQ of 71-85)

• 42% had no ID (IQ of 86 or above)

Translated to overall prevalence, about 1% of all U.S. children born in 2010 have autism without intellectual disability, and about 1.3% have autism with intellectual disability or borderline intellectual disability. By way of comparison, data from California’s Department of Developmental Services shows that about 1.2% of California children born in 2010 have entered the developmental services system as autism cases. The eligibility criteria for that system requires serious functional impairment and tends to exclude high functioning autism.

The following graphs illustrate how national autism rates have climbed among children in all three categories of cognitive functioning.

Above: Autism rates have climbed among children in all three categories of cognitive functioning. These estimates are based on the CDC ADDM data, multiplying percentages of each category of cognitive ability by overall birth-year autism prevalence.

In addition, the ADDM Network used a new case definition and data collection process for surveillance year 2018, which may have resulted in a modestly lower ascertainment rate. Unlike previous years, the new case definition did not ascertain ASD among children who were never identified as having ASD by a community provider.

“The ongoing, dramatic surge in serious developmental brain dysfunction among U.S. children portends nothing short of calamity for families, schools, adult support programs and even our economy and national security,” said Jill Escher, President of National Council on Severe Autism. “As a society, we are utterly unprepared to provide for the long-term needs of the ever-growing number of children disabled by autism, yet public health experts and policymakers remain conspicuously silent about this terrible phenomenon.”

The forces behind the increase in autism remain poorly understood, but research has made it abundantly clear that vaccines are unrelated to autism risk.

“Now that more than 2% of U.S. children suffer from this lifelong and often incapacitating neurodevelopmental disorder, it’s well past time to sound the alarm, as it has never been more urgent to identify causes, prevention, meaningful treatment, and lifespan care options,” Escher added.

The report is available on the CDC website cdc.gov.