Timon is now invaluable. He helps not only our sons but also helps us as parents better manage the struggles our children face on a daily basis.

Read moreGrowing Older, with Fewer Services

As autistic kids grow up, their needs can increase while services decline. A dad asks, is the system upside-down?

Read moreI am his whole world

Autism parents put a million details into the care of their beloved children. But what will happen when those parents are gone?

Read moreHow a simple vest made everything better

“I hear so many words of appreciation from those using the Vests, but also from those wanting a better understanding of autism. It is heartening.”

Read moreHow Many Broken Bones Is Enough?

By Duane Sloane

The worst is the passive aggressive guilt placed on parents when they become so overwhelmed they can no longer handle their child at home.

To those who may be among those who judge let me ask you: How many broken bones is ok? How many times should it be ok to be punched, pinched, purposefully vomited on?

How long should the siblings not be ever able to have friends over or sleep through the night? What’s the cutoff number for punching your six year-old brother?

Is there any PTSD involved for the rest of the family? How about the 11 year-old sister who is just used to the idea that her 16 year-old brother randomly strips naked and walks around naked, sometimes with an erection before we see him?

I contend that there are more selfish things than residential care. Like a lifetime of scars for everyone else to deal with as well. A fully staffed, well run residential facility is not a punishment to our children. It’s a decision filled with guilt and self-doubt.

But for those truly severe and beyond the cute toddler stage it is a heart wrenching sometimes necessary decision. Unless you have dealt day-to-day with violent severe autism in an adolescent, maybe reserve judgment. In fact just reserve judgment regardless.

There’s enough guilt already.

Severe Autism Needs "Institutions"

Severe Autism Needs “Institutions”

“Institution” can mean: “a facility where disabled people live in a confined setting, segregated from society, and without consent.”

But “institution” can also mean: “an organization that serves an important public purpose or societal need.”

Harvard is an “institution”

The YMCA is an “institution”

Mayo Clinic is an “institution”

St. Jude’s Hospital is an “institution”

The local high school is an “institution”

Those who attack autism-serving programs as “institutions” are not really anti-institution. They are just invoking a bogeyman to de-fund your essential disability services.

Don’t be fooled. High-quality “institutions” (the second type) devoted to the well being of the severely autistic —whether providing day programs, housing or medical care, whether in the “community” or in their own buildings, whether small or big — are exactly what we need.

NCSA Public Comment for IACC Meeting, July 2021

After a two-year hiatus, the federal Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee is set to meet later this month. As a public comment NCSA submitted the following letter (here as a PDF).

Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee

National Institute of Mental Health

Via email: IACCPublicInquiries@mail.nih.gov

Re: Priorities for the federal response to autism

July 1, 2021

To the IACC members:

The National Council on Severe Autism, an advocacy organization representing the interests of individuals and families affected by severe forms of autism and related disorders, thanks you for your service to the IACC in effectuating the congressional mandate to further federally funded autism-related research and programs, and ultimately improve prospects for prevention, treatment and services.

Dramatically increasing numbers of U.S. children are diagnosed with — and disabled by — autism spectrum disorders. In the segment we represent, those children grow into adults incapable of caring for themselves and require continuous or near-continuous, lifelong services, supports, and supervision. Individuals in this category exhibit some or all of these features:

ï Nonverbal or have limited use of language

ï Intellectual impairment

ï Lack of abstract thought

ï Strikingly impaired adaptive skills

ï Aggression

ï Self-injury

ï Disruptive vocalizations

ï Property destruction

ï Elopement

ï Anxiety

ï Sensory processing dysfunction

ï Sleeplessness

ï Pica

ï Co-morbidities such as seizures, mental illness, and gastrointestinal distress

Given the immense and growing burden on individuals, families, schools, social services and medical care, the autism crisis warrants the strongest possible federal response. Parents are panicked about the future. Siblings are often terrified about having children of their own, and/or the burden of providing lifelong care for their very much loved but highly challenging brothers and sisters. Schools cannot recruit enough teachers and staff to keep up with growing demand. Adult programs and group homes refuse to take severe cases. Vastly more must be done to both understand the roots of this still-mysterious neurodevelopmental disorder and to prepare our country for the tsunami of young adults who will need care throughout their lifetimes, particularly as their caring and devoted parents age and pass away.

With that in mind, we ask the members of the IACC to understand the priorities of our community. While this list is not exhaustive it represents many of the issues our families consider most urgent.

In the course of committee deliberations:

The amorphous word “autism” should never obscure the galactic differences among people given this diagnosis. The construct of “autism” — and it is just that, an artificial human invention contorted by political and historical forces — has thrown together into one bucket abnormal clinical presentations that often have nothing in common. A person in possession of intact cognitive abilities and/or adaptive functioning who suffers from social anxiety and sensory processing differences has no meaningful overlap with a person with severe intellectual impairment, little to no adaptive skills, and aggressive behaviors. The IACC should take care to make distinctions at every juncture where “autism” is invoked in a general way.

Zero tolerance for anti-parent prejudice. It has been alarming to witness the re-emergence of parent-blaming in some sectors of the autism community. Parents provide the lion’s share of support for both children and adults with autism and have been at the forefront of reforms aimed at improving the lives of those disabled by autism. Parents also most reliably speak out on behalf of the best interests of their non- or minimally verbal children. We ask that the attitude of the IACC be one of zero tolerance for the disturbing trend of anti-parent prejudice.

Honest language to communicate realities. It is crucial that discussions at the federal level retain the language the reflects our clinical and daily realities, such as the following examples we commonly hear from our families and practitioners: abnormal, maladaptive, catastrophic, chaos, low-functioning, suffering, devastating, panicked, hopeless, desperate, exhaustion, overwhelming, anguish, traumatic, bankrupting, financially crushing, suicidal, epidemic, tsunami. We stress this not to detract from the many positives found in every person disabled by autism, of course those also exist, but to ensure that the challenges of autism are never semantically erased.

As federal priorities are developed:

The ever-increasing prevalence of autism must be treated with the utmost gravity. Rates of autism that meet a strict definition of developmental disability have soared 40-fold in California over the past three decades. Rates of autism now exceed 7% in some school districts in New Jersey. There is overwhelming evidence for growing rates of disabling autism, and little evidence this has been caused by non-etiologic factors such as diagnostic shifts. We have both a pragmatic and moral duty to discover the factors driving this alarming, unprecedented surge in neurodevelopmental disorders among our youth and young adults. Clearly, vaccines and postnatal events are not responsible for the surge in autism, but many other factors warrant urgent attention so we can finally “bend the curve” of autism.

Maximizing the range of options available to our disabled children and adults. We need a broad range of educational, vocational and residential services to meet the very diverse needs and preferences of the autism population — and this includes specialized and disability-specific settings that are are equipped to handle the intensive needs posed by severe autism. The post-21services “cliff” is a gut-punching reality across our country. Lack of non-competitive employment options. Lack of day programs. Few or no housing options. No HUD vouchers. Little to no crisis care. A healthcare system and ERs utterly unprepared for this challenging population. Aging parents. Lack of direct support providers. Lack of agencies willing to take hard cases. All of this amounts to a nightmare for our individuals and families. Clearly, massive policy changes are needed across multiple domains to maximize options for this growing population.

A desperate need for treatments. Regrettably, the therapeutic toolbox we have today is largely the same as two decades ago. While a cure for autism is unlikely to ever arise owing to the early developmental nature of the disorder, the IACC should push for research on potential therapeutics that can mitigate distressing symptoms such as aggression, self-injury, anxiety, insomnia, and therefore improve quality of life while decreasing the costs and intensities of supports. The research may include medical treatments such as psychopharmaceuticals, cannabis products, TMS, and others, as well as non-medical approaches.

We appreciate this committee’s commitment to autism prevention, treatment and services, and for your consideration of our community’s priorities.

Very truly yours,

Jill Escher

President

NCSA Publishes Position Statement on Facilitated Communication

Below is the text of a new Position Statement published by the National Council on Severe Autism urging caution with respect to the authenticity of communications generated via the use of “facilitated” techniques. NCSA strongly supports the wide variety of independent communication efforts by all with autism but is concerned about the rising popularity of several non evidence-based modalities that depend on the support of an intermediary to generate output. For more information regarding Facilitated Communication and related approaches, in addition to evidence-based practices, please review our recent webinar on the topic here.

NCSA Position Statement on Facilitated Communication

NCSA enthusiastically supports efforts to improve independent communication by all those with severe autism, whether the communication is verbal, gestural, written, or through devices such as Alternative and Assistive Communication (AAC) technologies or a keyboard. We cannot support, however, a technique known as Facilitated Communication (FC). The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) defines FC as “a technique that involves a person with a disability pointing to letters, pictures, or objects on a keyboard or on a communication board, typically with physical support from a ‘facilitator.’” This support can take the form of touching the body directly (typically the hand, wrist, elbow or shoulder) or merely holding the letterboard. Studies dating back to the 1990s have repeatedly demonstrated that the products of FC reflect the (often non-conscious) control of the facilitator and do not represent authentic communication by the disabled person. At times, false statements generated by FC practitioners have resulted in devastating outcomes, including false accusations of abuse against parents and others.

For these reasons, NCSA joins ASHA, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, the American Psychological Association, the Association for Science in Autism Treatment and over a dozen other national and international organizations in opposing the use of FC.

We also urge caution with regard to newer variants of FC such as the Rapid Prompting Method (RPM) and Spelling to Communicate (S2C). Like FC, these methods rely on the intervention of a partner to facilitate the communication, and therefore carry the risk of conscious or unconscious prompting by the intermediary. Although practitioners regularly contend the output is the independent work of the persons being facilitated, we are concerned that to date no reliable research has confirmed the authenticity of the communications and that practitioners have systematically resisted calls for simple, straightforward verification studies. Such studies would include message-passing tests, where the disabled person is asked to produce information or answer questions the facilitator does not know the answers to, or tests where the facilitator was blinded. While NCSA does not oppose advances in any therapeutic field, we also ask that such advances be evidence-based, and subject to reasonable scientific scrutiny, especially given the tragic history of dangerous and ineffectual interventions of the past, including FC.

Recently, advocates have begun conducting and publishing studies that claim to prove the legitimacy of letter boarding with technologies such as eye-tracking devices, accelerometers, and electroencephalography (EEG). Orthodox speech and language researchers consider the use of such elaborate and marginally relevant technologies a distraction from the fact that practitioners refuse to submit RPM and S2C to basic validity testing. They are also concerned about advocates’ claims that autism is a motor, not cognitive, disorder, which has no support in the research literature, and that people with autism have normal cognition but suffer from short-term memory loss precluding them from participating in such tests.

Additionally, autistic voices are frequently cited as valid sources of representation for use in scientific research and policy development on the federal, state and local levels. However, some of the voices that are alleged to be representative of autistics are actually facilitated through RPM or FC, and should not be presumed valid.

References:

In-depth analysis of FC literature: www.facilitatedcommunication.org.

American Speech Language Hearing Association, Facilitated Communication and Rapid Prompting Method: CEB Position

https://www.asha.org/ce/for-providers/facilitated-communication-and-rapid-prompting-method-ceb-position/

Donvan J, Zucker C. In a Different Key. 2016 Crown Publishers, New York. (See Chapters 33, 34 documenting past abuses of FC.)

Fein D, Kamio Y. Commentary on The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida. J. Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics2014;33(8):539-542. (Here, paywalled but first page is available.)

Mostert M. Facilitated communication since 1995: a review of published studies. J Autism Developmental Disord. 2001;31:287–313. (The abstract reads: “Previous reviews of Facilitated Communication (FC) studies have clearly established that proponents' claims are largely unsubstantiated and that using FC as an intervention for communicatively impaired or noncommunicative individuals is not recommended. However, while FC is less prominent than in the recent past, investigations of the technique's efficacy continue. This review examines published FC studies since the previous major reviews by Jacobson, Mulick, and Schwartz (1995) and Simpson and Myles (1995a). Findings support the conclusions of previous reviews. Furthermore, this review critiques and discounts the claims of two studies purporting to offer empirical evidence of FC efficacy using control procedures.”)

Schlosser RW et al. Rapid Prompting Method and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review Exposes Lack of Evidence. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00175-w. (The abstract reads: “This systematic review is aimed at examining the effectiveness of the rapid prompting method (RPM) for enhancing motor, speech, language, and communication and for decreasing problem behaviors in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). A multi-faceted search strategy was carried out. A range of participant and study variables and risk and bias indicators were identified for data extraction. RPM had to be evaluated as an intervention using a research design capable of empirical demonstration of RPM’s effects. No studies met the inclusion criteria, resulting in an empty review that documents a meaningful knowledge gap. Controlled trials of RPM are warranted. Given the striking similarities between RPM and Facilitated Communication, research that examines the authorship of RPM-produced messages needs to be conducted.”)

Adopted by NCSA Board of Directors, June 24, 2021

“My 22 Year-old Daughter with Severe Autism Improved After an Experimental Treatment”

Madison during one of her therapy sessions.

NCSA interview with an autism mom about her daughter’s experience with transcranial magnetic stimulation

Background

In February 2019, NCSA published a blogpost called, "Autism: Miswiring and Misfiring in the Cerebral Cortex," by Manuel Casanova, MD. He explained the evidence that autism can be rooted in pathologies of brain development, specifically abnormal micro-structural development of the “minicolumns” of the cerebral cortex, and further that this physiological defect had potential implications for therapeutics.

Dr. Casanova discussed that the cerebral cortex is the part of the brain that enables us to process sensory information, engage in complex thought and abstract reasoning, and produce and understand language. It accounts for our volitional actions including those that allow us to adapt to our immediate environment. But in autism we see the failure of connections — cells in the cerebral cortex are not able to coordinate their actions with other cells in their surroundings.

He then explained that these findings may suggest a therapeutic intervention based on transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). TMS works on the principle of induction of electricity. A strong magnetic field induces current through anatomical elements in the cerebral cortex that act as conductor. Due to the geometrical orientation of anatomical elements within the periphery of the cortical minicolumns, inhibitory elements are stimulated when using low frequency stimulation. This intervention allows us to rebuild the “shower curtain” surrounding the minicolumns.

He said that several hundred high functioning ASD patients have been treated with TMS with positive results, primarily in terms of improving executive functions and reducing perseveration.

This interview with autism mom Jan Kasahara is something of a follow-up to Dr. Casanova’s article. It is not meant to offer medical advice, and does not constitute an endorsement of this intervention. Rather, the purpose of this interview is to highlight the extremely urgent need for therapeutics for severe autism, and that this therapy may warrant greater scientific attention for low-functioning individuals.

Interview

NCSA: Jan, we wanted to give our community a chance to hear about your experience, because you have a daughter who has who is severely impacted by autism and who underwent this experimental treatment, which is very unusual. Please give us a bit of background about Madison.

JK: Madison is 22. We adopted her from China as a baby, and at the age of three she received a diagnosis of autism. She started talking and then stopped. She started hand flapping, spinning in circles, not wearing clothes, climbing on everything — pretty much showing many signs of low functioning autism. And since then, it's been a struggle to try and find something to help her.

She has severe OCD. She will hit her chin if she can't put all of her movies away. She will get upset in the car if we don’t go a certain direction. She would be constantly upset, often screaming, having trouble trying to show me what she wants. She can't point. She has trouble with tags on her clothes, she'll only wear crocs and won’t wear regular shoes. Very little eye contact and she can't really do anything functional, for example she can't brush her hair, she can't dress herself, she cannot help with anything around the house. She basically would sit on the couch and do YouTube all day or movies.

NCSA: Obviously one can see why a parent in your situation would be very eager to find something that could help her.

JK: I think the number one problem with her is language. I was really hoping to find something to help her achieve some form of language because I think that is a lot of her frustration. Also, she has a huge amount of anxiety, which was very, very high. She seemed like she'd always struggle with that or depression. She had no initiation. She didn't really care about people or what she was they were doing, so her quality of life was just so low. And I was just trying to think of anything that would help her quality of life.

NCSA: So what how did you come across the idea to try TMS?

JK: To be honest, I was on YouTube, and like any autism mom, trying to find anything that I could possibly find. And I fell upon a clinic based in San Mateo, which is not far from our home in the Bay Area. And there was also a little blurb about it from the TV show The Doctors about a young girl who had autism, and TMS helped her start speaking.

I am definitely one of those moms who is unafraid to experiment. So I researched it and spoke with the clinic’s director. So I met up with him and I felt really comfortable with him.

NCSA: To be clear, this treatment was not covered by insurance, just a private pay enterprise on your part.

JK: Our claim was denied but we are resubmitting it with more information. The six-week treatment was more than 10,000 dollars.

NCSA: Please tell us what the therapy consisted of, and any difficulties experienced by Madison.

Well, first they need to do an EEG to look at her brainwaves to see more precisely what is going on. I’m hardly a neuroscientist but I’ve learned that with a lot of kids with autism, they find that their brain waves aren't functioning completely, which is associated with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. The waves are very flat.

In the EEG she had to wear a tight cap on her head with little electrodes. So we practiced at home, putting a bathing cap, shower cap and knitted beanie, anything to try and get her used to have something on her head. But once we got her in there, they were so sweet and they really made it easy for her. They need 10 minutes of quality data with her eyes closed, motionless and quiet. With Madison, the process took from 10 minutes to 40 minutes depending on how calm she was that day.

The EEG showed that basically her brain waves were pretty flat. He could tell also by looking at the brain waves that she wasn't sleeping, had a lot of depression and anxiety. The clinic had not worked with a lot of kids on the spectrum this severe, and they couldn’t promise anything regarding the treatment, but I decided to just go ahead. It was worth a try.

They developed a treatment plan based on the EEG, such as where they put the magnet, how strong they want to make it. In her case, they put it in the front part of the cortex and behind in the back of her head. The magnet is like a heavy, flat wand, with a handle and makes a clicking sound as they put it against the head to stimulate the brain.

It was of course challenging to keep Madison sitting still. I'm not going to say it was easy. She did get upset. The doctor actually made sure that he brought in Oreos, her favorite, to entice her to stay in the seat, which is like a leather recliner chair. They also have a weighted blanket and toys and would play movies and music videos. Some of the kids end up running down the halls and they just go retrieve them and bring them back and they really try their best.

NCSA: So how long did Madison have to sit in the chair for each session?

JK: About 30 minutes.

NCSA: Yeah, that would be hard for a lot of our kids. How many sessions did she do?

JK: So 30 minutes, five days a week for two weeks — that was the first set of sessions, and then we did two more sets. About 30 treatments altogether.

NCSA: But as you said, you’re a mom who is willing to try almost anything, you’re taking one for the team. So did you notice any changes in Madison right off the bat?

JK: It seemed like her anxiety did go down. I noticed that she was a lot calmer and she seemed more affectionate, which was something different. She was actually cuddling with me on the couch, which she had not really done before, and she was looking into my eyes more. She didn't seem as fearful like she was. So those were the main things in the very beginning. A lot of the fear, a lot of the depression and anxiety had seemed to go down and she seemed to be more affectionate.

NCSA: Then after the three sets of treatments?

The treatments ended in March and now we’re in June. I noticed her speech started getting a little bit clearer, including some new words. One night we were in her bedroom and I would hold up a book and she said “book.” And then I would hold something else like a bear, and she'd say, “bear.” It was so exciting, and she was just so fun. She was so happy.

She seemed to have more initiative. She had gone into the bathroom and I noticed that she'd taken the toothpaste and put it on her toothbrush, something she had never done, and she started brushing her teeth back and forth. So even her motor planning got better. Before she would just bite her toothbrush, but I actually saw her brushing back and forth. Then she'd take a hairbrush out and she'd start brushing her hair. That was just too much. That was something she would never do. So I could see that there was a lot of initiative happening. And that was very exciting.

I took her to the store yesterday and I thought to myself, she's not rocking back and forth on her feet like she normally does. She’s normally stimming with her hands, making all kinds of echolalia, walking into people. And she was just standing there, calm. It was so strange.

Recently she got all the dolls out of the garage. She had never played with dolls before. She brought them into the family room and she started pretend play. She started brushing their hair and changing their clothes and went and got the bed and put them in the bed - without anybody prompting her.

At school, they've told me they can't believe how great she's doing. She's not running into other classrooms like she always did. She's staying in the classroom. She's actually helping wash the dishes, which she's never done. She can ride the bike. She used to scream for somebody to help her get on the bike, but now she just gets on the bike by herself and goes. She doesn't scream anymore.

NCSA: The reason we wanted to publish something about your experience is not to make any claims about the treatment (this is classic n=1) but to stress that for kids like ours the need for progress is so urgent — we desperately need to find interventions that can increase functional capacity, improve quality of life, alleviate terrible symptoms. We need a more intensive research effort to find valid interventions.

JK: Absolutely! Our kids are suffering every day. They are behind a wall where they can't even express for themselves what's going on. They're depressed. They are dealing with trying to move their bodies and their bodies won't do what they want to do. They're hitting themselves. They're impulsive. These are kids who are going to need immense amount of help in the future. And if we can't find help for our kids, they're going to have a terrible life. They're going to suffer, and the last thing we want for our children. More and more kids have an autism diagnosis. The need to help them is absolutely desperate.

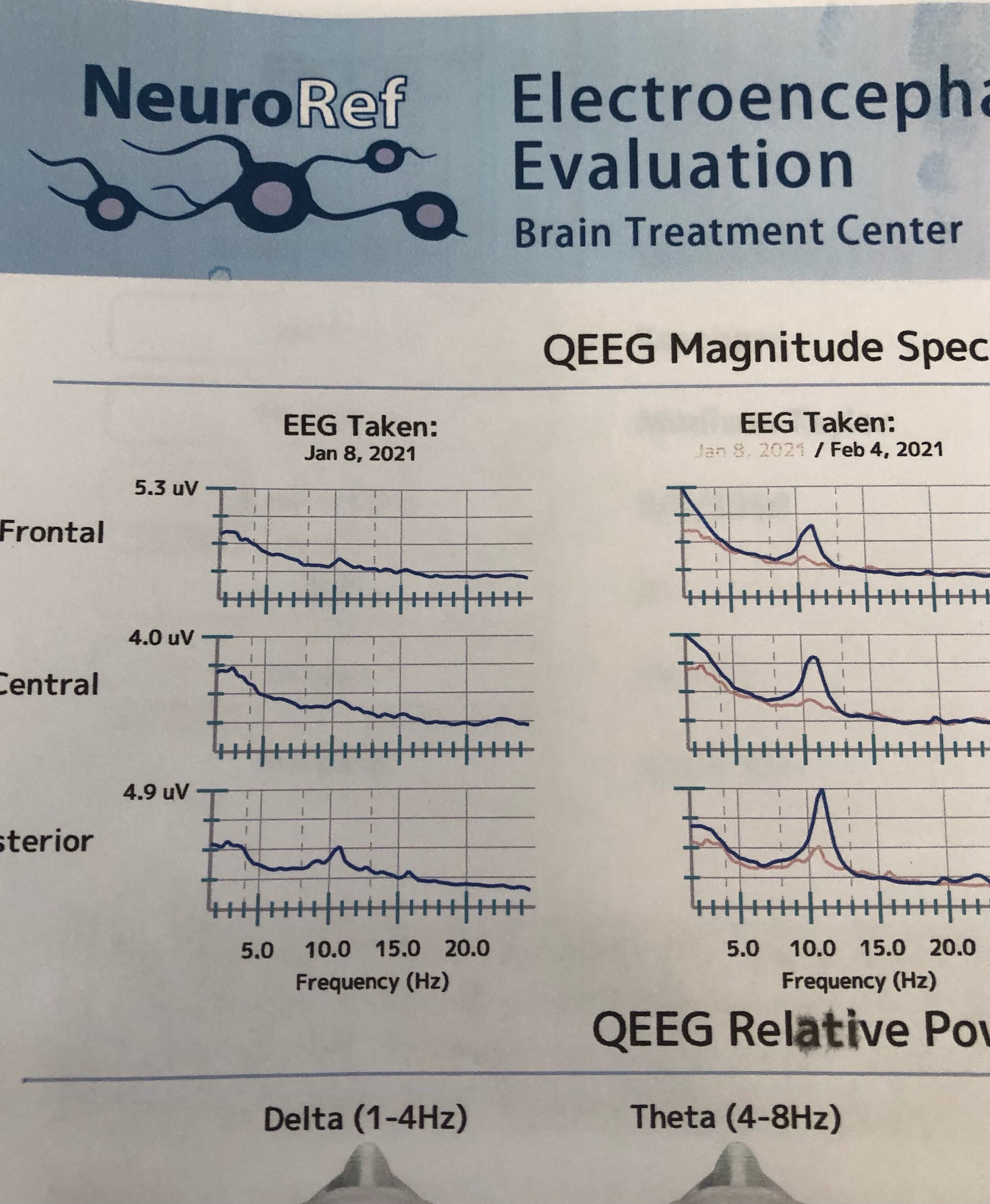

Changes in Madison’s EEG seen after a month of treatments.

NCSA: Did Madison’s EEG change after the treatment?

JK: Yes her EEG did change. The brain waves increased. So there seems to be an objective measure of improvement and not just our anecdotal observations.

NCSA: I wonder if the benefits you are seeing will be lasting.

JK: We don’t know. We shall see.

NCSA: Jan, thanks so much for taking the time to share your experience with our NCSA community.

_______

For further reading:

Casanova MF, Shaban M, Ghazal M, El-Baz AS, Casanova EL, Sokhadze EM. Ringing decay of gamma oscillations and transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy in autism spectrum disorder. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2021 Jun;46(2):161-73.

Casanova MF, Shaban M, Ghazal M, El-Baz AS, Casanova EL, Opris I, Sokhadze EM. Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy on Evoked and Induced Gamma Oscillations in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences. 2020 Jul;10(7):423.

Casanova MF, Sokhadze E, Opris I, Wang Y, Li X. Autism spectrum disorders: linking neuropathological findings to treatment with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Acta Paediatrica. 2015 Apr;104(4):346-55.

Robison, John. Blogpost: TMS and Autism. http://jerobison.blogspot.com/p/use-of-tms-transcranial-magnetic.html

Disclaimer: Blogposts on the NCSA blog represent the opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily the views or positions of the NCSA or its board of directors.

NCSA Letter in Support of NJ Bill Allowing for Videocameras in Group Homes

New Jersey state capitol.

New Jersey State Senator Vin Gopal

New Jersey State Senator Stephen M. Sweeney

New Jersey Assemblymember Craig Coughlin

New Jersey Assemblymember Joann Downey

Via email to: sengopal@njleg.org, sensweeney@njleg.org, aswdowney@njleg.org, asmcoughlin@njleg.org

June 11, 2020

Re: Support for Billy Cray’s Law, Bill NJ A4013

Dear Senator Gopal, Senator Sweeney, Assemblymember Coughlin and Assemblymember Downey,

The National Council on Severe Autism (NCSA) has followed with great interest and fully supports Billy Cray’s Law, Bill NJ A4013, the effort in New Jersey to provide for electronic monitoring devices (EMDs) in group homes serving adults with developmental disabilities, including autism.

NCSA is a voice for the disabled who have no voice — specifically, the growing population of Americans disabled by severe forms of autism. Those with severe autism often have minimal language, low cognitive ability, severe functional impairments, and dangerous behaviors, including aggression, self-injury and property destruction. They typically need 24/7 care, for life, having little capacity to care for themselves or earn a living.

Tragically, one issue too often seen in our care system is neglect and abuse in group homes and other settings. Prevention of abuse and neglect, in addition to ensuring proper procedures and accountability, requires a multi-pronged approach including adequate hiring, training, pay, and supervision practices by all agencies responsible for the care of adults with autism/DD. One element of a healthy training and supervision practice is the use of EMDs in common areas with the approval of the home clients, and in private areas with approval of the individual resident. Normally, EMDs would not be necessary inside of residences, but one clear exception to that rule is the case of residents with impaired ability to communicate or advocate for themselves. In those cases, visual documentation compensates for the absence of information that could be gleaned from the client.

The benefit is three-fold: first, it would significantly enhance abuse and neglect prevention strategies as a training tool and a mechanism for instructive feedback for staff. Second it would help deter any neglectful or abusive behavior on the part of staff, and render programs generally more accountable to clients and their guardians. It would also assist in providing evidence in those cases where abuse or neglect is suspected, again, compensating for the fact that the minimally or nonverbal clients are incapable of communicating their circumstances and remain utterly dependent on others for their protection.

The bill strikes an important balance between protecting people's privacy and protecting their overall well-being. EMDs would be installed only upon consensus of clients, and in private rooms, only upon request of the residents. The recordings are retained by the group home for only a period of 45 days. Staff members would need to provide express written consent to the use of the EMDs in the group home's common areas, as a condition of the person's employment. A prominent written notice would be posted at the entrance and exit doors to the home informing visitors that they will be subject to electronic video monitoring while present in the home. The Department of Human Services would conduct on-site device inspections. The Ombudsman for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities and Their Families, the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities, and the group home provider community, will work together to establish and publish guidelines for the development of internal policies.

Billy Cray’s Law is a very welcome addition to a developmental disability system that desperately needs more safeguards for vulnerable clients. Thank you for your commitment to the welfare of adults with severe disabilities and your consideration of this important bill.

Very truly yours,

Jill Escher

President