One way out: an integrated care approach

By Katherine Troyer

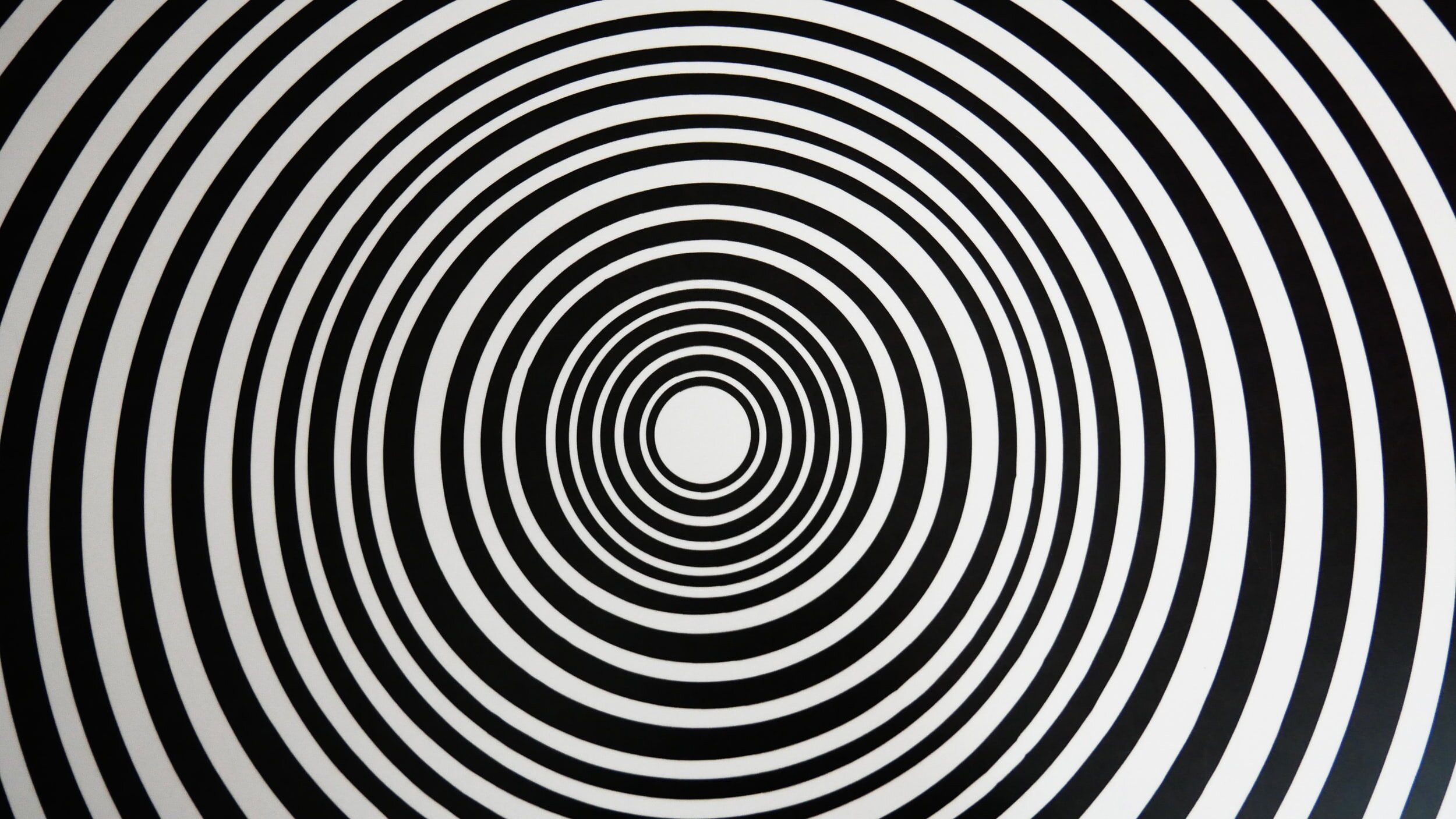

It is what I call “the circle of strife.” Our loved ones with severe autism access services only to have them returned to us because they are “too” challenging.

We know the phone calls will come, informing us of some disruptive, gut churning scenario.

Mothers bear the brunt of those phone calls. Mothers are everything and mothers are nothing. We are still often blamed, and our ideas and insights minimized or dismissed. Yet we are often expected to provide the explanation, the resolution. Make it all better, Mom!

I am the mother of an adult son with severe autism and severe intellectual disability. When lost in that circle of strife or consumed by anxiety awaiting that phone call, I have tried to ground myself in what I know, what I have learned.

1. I know when my son is experiencing a severe behavioral crisis, he is suffering. To me, it is a “medical” crisis, not a “behavioral” one. No behavior plan, no data collection, no graph is going to alleviate that suffering. Over time we have increased his risperidone, and have added topiramate, propranolol and quetiapine fumarate. My theory is that my son has been helped by antipsychotic medication because he may experience psychotic episodes—distressing visual or auditory hallucinations, or delusional thinking. With appropriate medication (and supportive, trusting relationships), he has been able to attend school and now day program, go on family vacations, participate in community activities, and for over a year now, reside in a group home.

2. I know environment counts. We want environments that are calm, structured and predictable, not overcrowded and under-staffed. Programs that use positive reinforcement and not punishment. That emphasize the building of trusting, caring RELATIONSHIPS. That understand how to safely de-escalate situations. That engage individuals in meaningful activities, and that provide opportunities for community outings, including access to nature. Professionals like occupational therapists, exercise physiologists and music and art therapists could be employed as consultants to assist providers in developing meaningful programming.

3. I know the health and mental health care systems have struggled to serve my son. When our loved ones need medical care, push for that test or scan. Hospitals are not prepared to provide the necessary 1:1 supervision if family or provider cannot meet that need; they should have trained staff on call to provide such supervision and care. With respect to mental health care, there are too few professionals willing to work with this population, and fewer still with the knowledge and experience needed. There are far too few psychiatric inpatient beds for individuals in mental health crisis.

An integrated care approach may provide a solution, offering one integrated care “home” where individuals can receive both quality health and mental health services. The clinic would be a repository of up-to-date knowledge and expertise. It could be linked to designated inpatient beds for health and mental health crises. Staff could provide ongoing training and consultation to families and providers, and both would have a resource to contact for information and help.

We need integrated care solutions to end the “circle of strife” and move toward a system of care that is committed to providing meaningful and therapeutic services to persons with severe autism.

Katherine Troyer lives in New Jersey.